Paula Garcia Defies Death Once More

Words by Lameah Nayeem

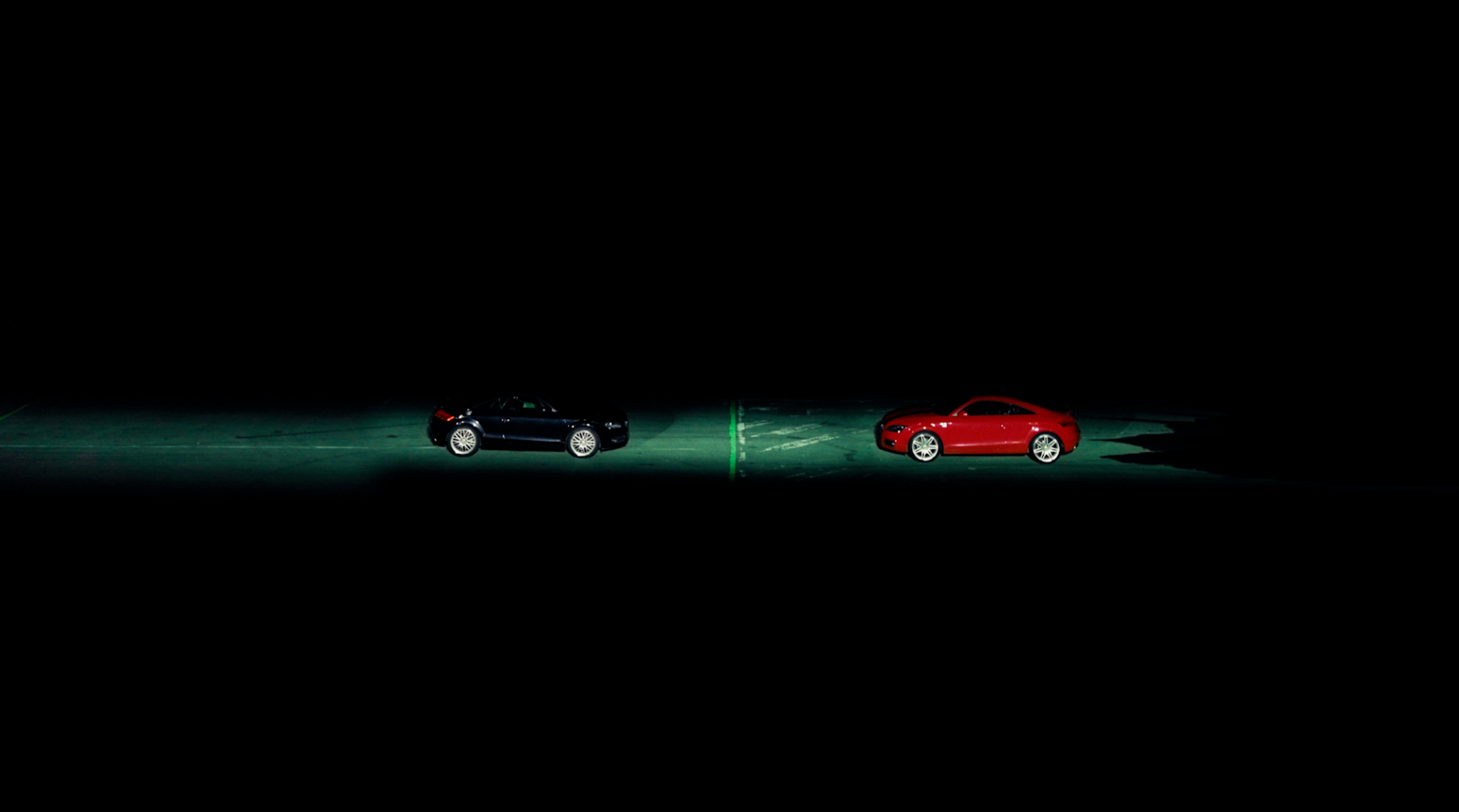

Still from Crash Body, short film, 2026. All images courtesy of Subversus and VERSUS

Time and time again, Paula Garcia emerges from the wreckage alive. When she first performed Crash Body and livestreamed it from a São Paulo gallery in 2020, Garcia stepped out of her mutilated Audi TT relatively unharmed. Performing it live a second time at Dark Mofo in 2025, she wasn’t as lucky. The unpredictability of calamity becomes an inevitability in Garcia’s work as she choreographs a back-and-forth between herself and fellow stunt driver César Hernández. Circling each other in twin vehicles, they narrowly avoid collision until the final act culminates in a head-on impact. Garcia’s brand of performance art teeters on the edge of catastrophe as she courts death as closely as she dares without yielding. Produced by Subversus and directed by VERSUS, the most recent iteration of Crash Body was adapted into a short film.

Below, Garcia chats with Lameah Nayeem about her preparation for the stunt, the adjacency of performance art to danger, and lessons on mortality.

LAMEAH NAYEEM: What inspired Crash Body?

PAULA GARCIA: Crash Body was a performance I created involving a frontal collision of two cars. My first experience working with cars, in 2020, emerged directly from earlier works in my Noise Body series. In those performances, I wore iron armor with magnets attached to it, while collaborators threw nails at my body. Through the physical experience of those performances, an image gradually took shape: the idea of wearing a car. In this sense, the car enters my work as a kind of shield or garment. But unlike the earlier performances, this protocol involved a different decision. Entering an industrial structure at speed became a conscious choice, made by me and shared with my collaborator, the professional stunt driver César Hernández, who drove the second car. Here, the collision is not something that happens to me; it is something I choose to enter.

LN: What goes through your mind when you're behind the wheel?

PG: It is difficult to say exactly. For me, the moment of driving is always marked by a very concentrated state. I often compare it to martial arts: being fully present, attentive to timing, to movement, to what needs to be done at each precise moment. There is very little space for distraction or doubt.

What remains truly unpredictable, however, is the impact itself. No amount of preparation can help you anticipate it. The collision is extremely violent and it breaks that focused state in an instant. That moment of impact is where control gives way to something raw and uncontrollable, and it is precisely there that the work reveals its intensity.

LN: Crash Body has been performed several times, though resulting in injury. How do you prepare for a performance that continuously puts your life on the line?

PG: My work has always dealt with questions of physical and mental limits. With the project at Dark Mofo, I was not planning to repeat it, because it is an extremely violent protocol.

The first thing I asked the Brazilian and Australian stunt teams was whether it would be possible to push the image a bit further to reach an even more striking visual moment. With this work, I truly reached a limit, and I did not feel well for several days afterward. This is despite the fact that I train a lot. I am not young — I am 51 years old — and physical training is essential for this kind of work.

I can say that I came out of this work shaken, almost broken, but I say this calmly. All the risk was carefully calculated, no one was seriously injured, nothing was physically broken. And yet, I was profoundly affected. It was new, unexpected, and I am still trying to understand what exactly took place in that second encounter with the limit.

LN: Where does performance art cross the line into real danger?

PG: If we look at the history of art, especially in the 1970s and 1980s, there are many artists who worked intensely with these kinds of protocols — Marina Abramović, Tania Bruguera, among others. Many of these works operated very close to real danger, sometimes placing the artists in situations where death was a real possibility. I have deep respect for these artists; they are very important references for me.

In my own work, however, I try to address risk and danger within clear safety coefficients. In Crash Body, the central question was: what is the maximum speed we can reach without creating an unacceptable risk of fractures, internal bleeding, or serious physical harm for me and for the other driver, César?

The cars were modified specifically for the collision. The fuel tanks were adapted, the safety belts and racing seats were modified, and the vehicles were structurally reinforced. The cars were truly designed to absorb impact and distribute force in a way that protects the body as much as possible. In this sense, I see a difference between some of the works from the 1970s and 1980s. In my work, violence and risk are present, but they are always negotiated through preparation, calculation, and shared responsibility.

LN: Risk, of course, comes with reward. What is the most rewarding part of Crash Body?

PG: One of the most beautiful aspects of this work has been listening to the accounts of others. Because of the amnesia immediately after the collision, I have no memory of how people reacted. That absence is permanent.

Now, I encounter the work through the voices of others. Through messages from people who were there, through everyone involved, through the journalist from The Guardian who wrote a very moving article about the work.

I don’t create performances thinking about how they will circulate in the world or how they will be received. I don’t want that kind of control. The work has to exist first because it is necessary for me as something in my body, in my life, demands it. What comes afterward belongs to the world.

LN: The work ultimately reminds us of the precarity of life — but has it taught you anything new about mortality after the many times you've performed it?

PG: Yes, no. This is a very good question. After the work, in conversations with psychoanalysts, they brought this very clearly to me: the notion of mortality. I have always carried a strong drive to push forward, to do things. And this work confronted me very directly with my mortality.

It introduced a powerful awareness of finitude. I came out of the experience extremely fragile, but it was a kind of fragility I had never known before. Not a weakness, but a vulnerability that awakened something else in me.

That fragility brought with it a renewed desire to live. A desire to be present. The work took me to a place I had never been before. A place of exposure, of mortality, of truly understanding and feeling, in my own body, how harsh that limit is. And at the same time, how strangely liberating it can be. It was as if touching that edge — feeling how close everything can be to breaking — opened a deeper connection to life itself.

Crash Body can be viewed here.