Everything is Pink at Ota Fine Arts Tokyo

Words by Lameah Nayeem

Follow A-M Journal’s features editor, Lameah Nayeem, as she traverses Tokyo’s art districts.

'Pink' Installation View, courtesy of Ota Fine Arts Tokyo. Photo by Kanichi Kanegae

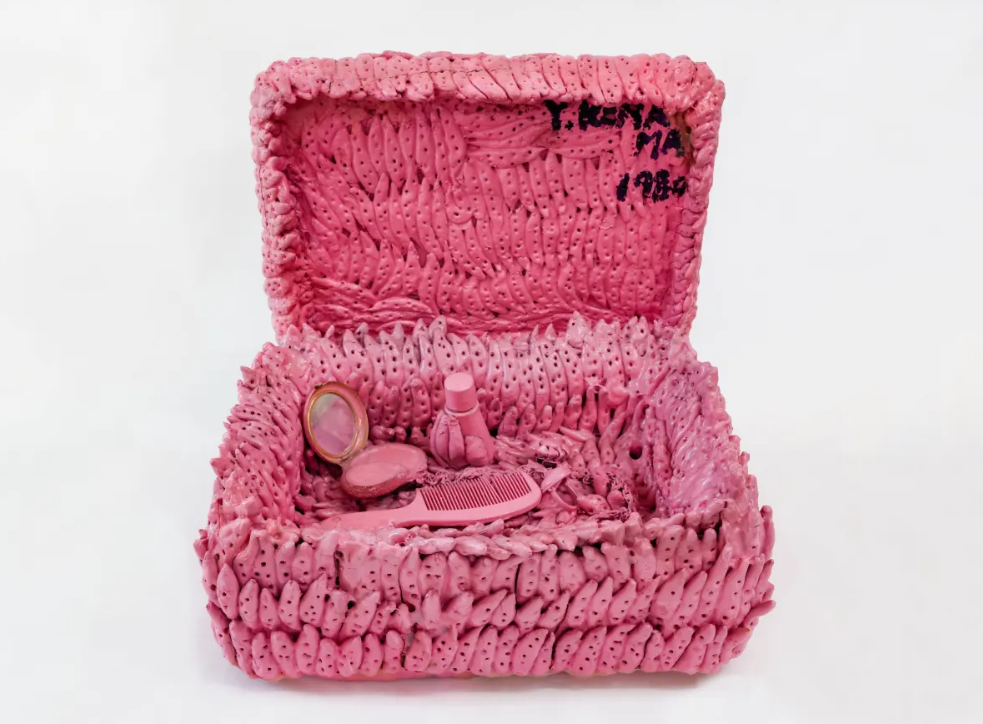

Pink is a linguistic phenom. Pink is the alien cosmetic box and its innards. Pink makes up all shades of the rainbow in Ota Fine Arts Tokyo's newest group exhibition, Pink. Throughout history, pink has been the most modular of the colours in its shifting meanings: innocence to eroticism, commonplace to queer, sophisticated to satirical. Located along a belt of art spaces in Roppongi — Tokyo’s shiny, new gallery district — Ota Fine Arts Tokyo’s Pink goes toe-to-toe with these established connotations, deconstructing their instability to challenge how we consume the colour across contexts.

The colour pink was seldom valued by cultures prior to the 17th century. As a result, specific names for pink hues did not emerge until the late 17th century when colour terms like 'rose' entered Western European vernacular. Japan had developed native descriptors approximately a century earlier, including sakura-iro 桜色 (cherry blossom colour) and momo-iro 桃色 (peach colour). As BuBu De La Madeleine critiques through her work, the imported English term ‘pink’ now dominates everyday usage in Japan, despite Japan’s head start. De La Madeleine mobilises the crested ibis as a proxy for linguistic erasure. The once near-extinct bird, prized for its coral-streaked plumage, recurs as a mournful figure in her paintings. Often tearful and splayed outwards, the ibis is De La Madeleine’s vessel for her anxieties surrounding the erosion of cultural legacies once enshrined in fauna and language.

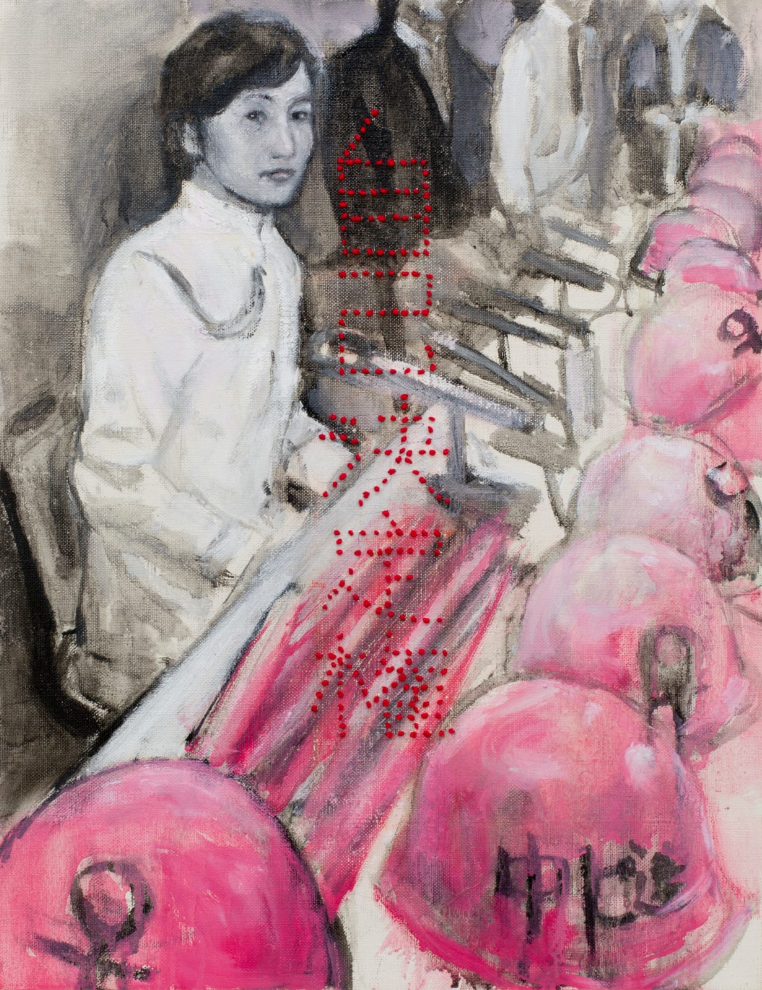

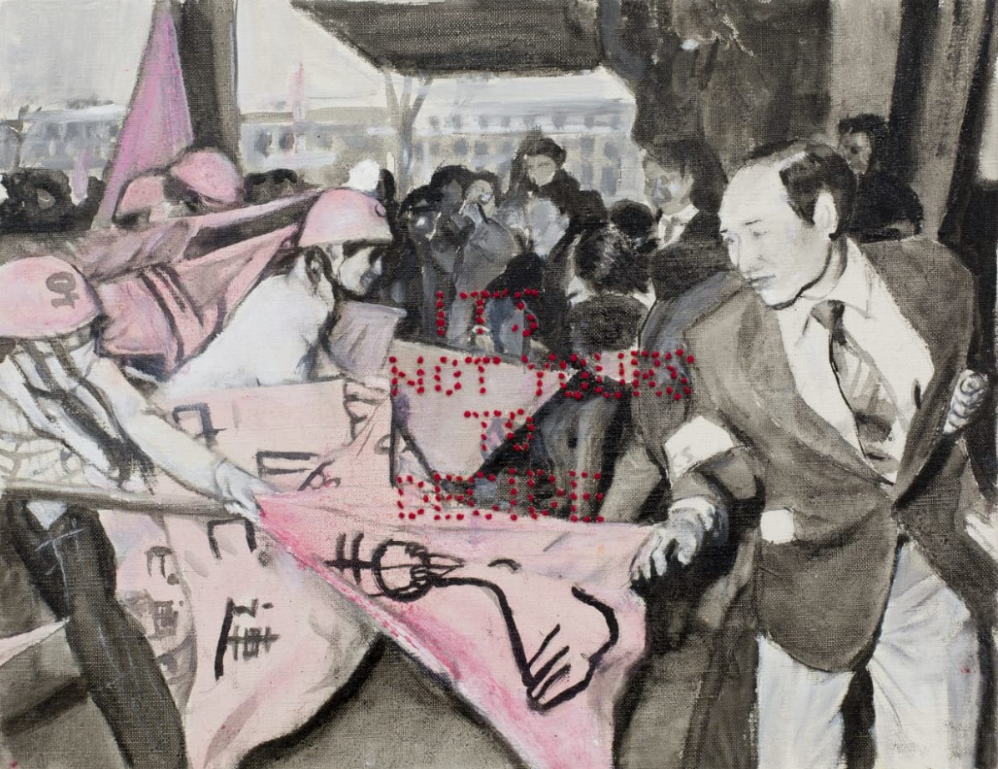

Yoshiko Shamada, widely lauded as Japan's foremost feminist artist, decodes the entanglement of colour, protest, and politics. In Charge! Red knots (2023) and Right of Self-determination Red knots (2023), Shimada cogitates mostly in monochrome, depicting the 1970s women’s activist group Chu-pi-ren (Women’s Union for the Liberalisation of Abortion and Legalisation of the Pill) across a series of scenes. Against the greyscale backdrops, their helmets puncture the compositions in sharp splashes of fuchsia. Chu-pi-ren garnered an unsavoury reputation for what were deemed sensationalist tactics: confronting unfaithful husbands at their workplaces, staging sit-ins, and appearing in public marches dressed in with white, military-esque attire paired with pink hard hats. Shimada rejects the notion that pink diminishes the gravity of women’s self-determination — a sentiment echoed by the Japanese media during the ‘70s and echoed decades later in The Washington Post journalist Petula Dvorak’s infamous comments on the 2017 Women’s March: “Please, sisters, back away from the pink.” So often tethered to youth and play, pink is frequently framed as a liability, a colour thought to minimise women’s political demands. Shimada needles against this logic, embroidering her works with decrees like, ‘It’s not yours to decide’. Pink’s reputation as an ‘un-serious’ colour is inseparable from the historical devaluation of girls and women. It is precisely this inheritance Shimada combats as she redefines pink as a symbol of defiance and fighting spirit.

Often romanced by the chromatic turns of video and mixed media, Ming Wong adopts the persona of a fictional porn actress in Fake Daughter's Secret Room of Shame (2019) to terraform gender norms. Displayed on three phones affixed to a tripod, Wong, a male artist, appears in haphazardly donned wigs and a slash of red lipstick. Oscillating between a traditional pink kimono, low-cut floral dresses, and appearing topless with prosthetic breasts on display, Wong appropriates the visual codes of Japan’s 1960s pink films — independently produced erotic cinema — and the subsequent Nikkatsu Roman Porno series.The work traces the nomadic path of visualised pleasure from cinema screens to hotel-room televisions to home video, and now to online platforms accessed through personal devices. Of course, Wong’s presentation also nods to the eros of pink: his unabashed depiction of the body's erogenous zones, his floral motifs which allude to their role as the sex organs of plants, his application of cosmetics to mimic blushing. In performing the role of a woman subject to male desire, Wong satiricises the hegemonic gaze inherent to pink film. By introducing expressions of cross-dressing that had been circulating in Asian subcultures since the 2010s (such as Japan’s otokonoko (男の娘) and the Chinese term wei niang (偽娘) — literally meaning boy-girl), Wong subverts the power play embedded in heterosexuality. In Wong’s hands, pink no longer marks subjugation to male pleasure, but indicates where binaries of desire and performance no longer apply.

Ming Wong, 'Fake Daughter’s Secret Room of Shame', 2020. Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts Tokyo

To engage best with an exhibition, you might enter with no assumptions. When viewing Pink, it’s not possible to abandon presuppositions or maintain pre-existing notions on the subject. Ota Fine Arts Tokyo deftly negotiates pink’s plurality, relating a single colour to our infinite complexity — our most subversive and mutable values, our virtues, our vices.