Paige K. Bradley on Reception and Perception

Interview by Geoffrey Mak | Introduction by Lameah Nayeem | Photography by Olivia Parker

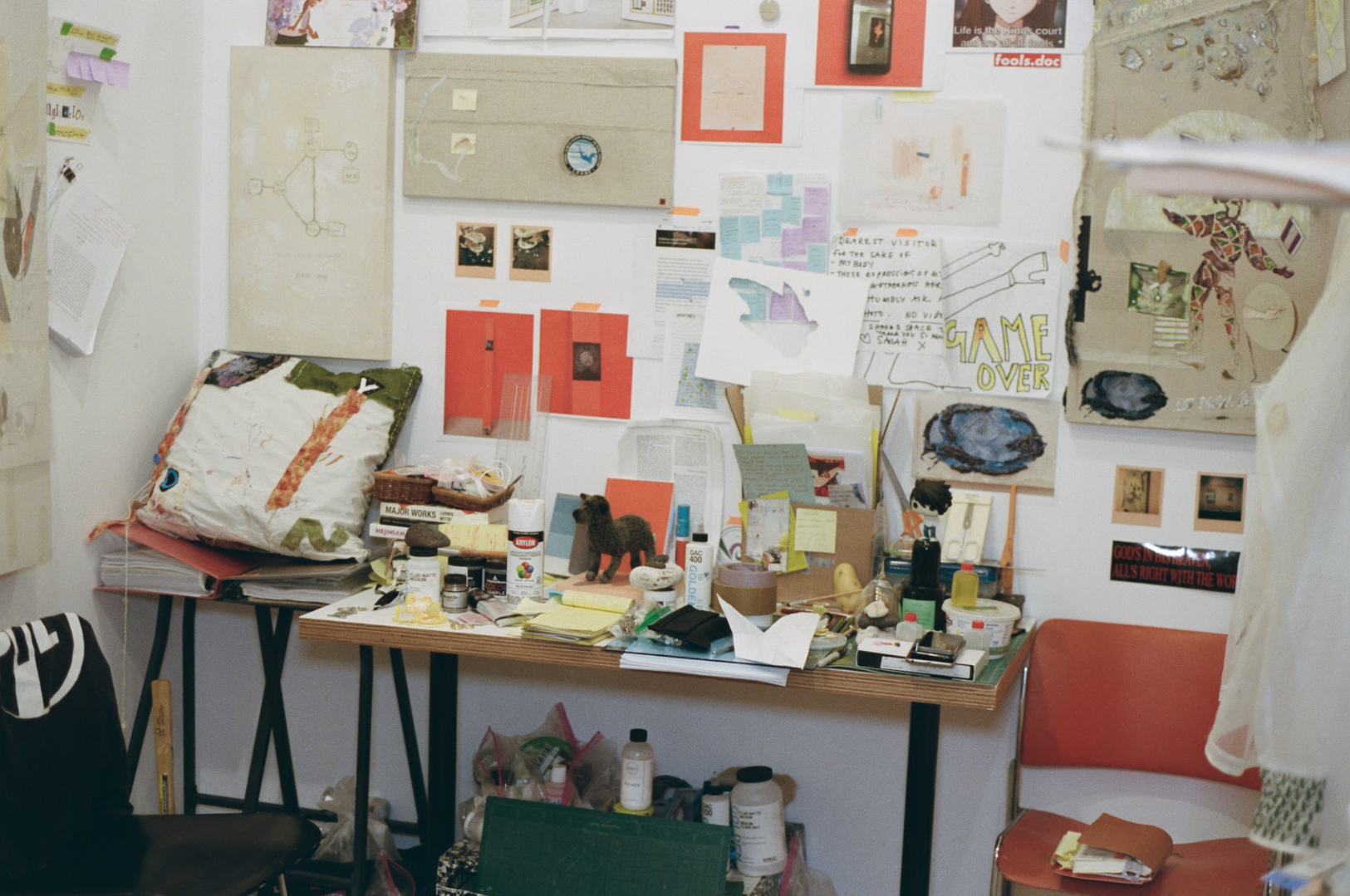

Based in the United States, Paige K. Bradley is an artist and writer fixated on how meaning behaves across its life stages. She observes its conception to its implantation within her artworks, where meaning often assumes its own posture seemingly without permission. Heavily research-based and overflowing with pastiche and ornamentation, her visual language embodies the syntactical bizzarria needed to translate the undefined into concrete matter. Her visual artworks build on her published writing, which has appeared in The New York Review of Books, i-D and Art Forum, and manifests in a multidisciplinary portfolio spanning painting, printing, collage and installation.

Bradley is attuned to the symbolic currency of an image and the circumstances in which that currency waxes and wanes, exploring the instability of allegory and the elusive resting point of the idea lurking behind the artwork itself. In an increasingly digitised world, Bradley’s iPhone voyeurism, critique of conspiracy theory culture and allusions to 2010 meme culture centre on the hubris of the 21st-century spectator. While obeying certain conventions of contemporary form, she fashions popular culture and jester insignia into motifs that invite irony, sincerity and social criticism for a jaunt through her screen-burned imagination.

Her noisy compositions extrapolate the friction between concept and representational devices, authenticity and inauthenticity, value and entropy. In what she dubs the ‘IRL-experience’, Bradley reframes our reality as the in-between where ideas and expressions are metabolised once confronted by popular thought.

Geoffrey Mak: I'm curious about the role of memes in your work because a meme, or an object on the internet, isn't valuable because it communicates an objective truth that everyone agrees on. Its value lies in the energy it carries – the velocity with which it circulates in countless different contexts. How much do you consider these structures, and how do you incorporate them into your practice?

Paige K. Bradley: I use a really old-fashioned meme format in my work. I like templates for making images, that's really interesting to me. This idea that you're kind of working with a preset, material or icons or signifiers – that's pretty common in art history. In the Renaissance, it would be like Bible stories. During Impressionism, it was scenes of bourgeois life or gardens. In different eras it takes on different forms. I like to use something that is fairly common because whilst I might have specific interests, there needs to be some kind of hook or lure that is recognisable.

GM: I know the word allegory is very important to you. How do you define allegory, and how does it play into your work?

PKB: One foundational reference for me is an article written by Craig Owens for October in the Summer 1980 issue, when he was articulating the emergent post-modernism at the time. There's a dictionary definition of allegory, but the way that Owens is articulating allegory is rooted in his reading of Walter Benjamin, particularly the Ursprung des deutschen Trauerspiels, which translates to The Origin of German Tragic Drama. Benjamin discusses allegory as emerging from the Baroque, characterised by an excessive accumulation of information and an overabundance of signifiers.

Albrecht Dürer's engraving Melencolia I (1514) is a common visual reference. In this work, there are too many things and objects sitting at the feet of the figure. There are a lot of signifiers, and there's a melancholy that is implied because these things don't cohere. There's an instability to the allegory; a kind of desperation of wanting to make things cohere. This can also be applied to Modernism. Modernism was characterised by the city, of being in the town, surrounded by people and things unfamiliar to us. It’s a constant, and it's churning. There's too much going on. We don't know how to deal with meaning – it's a crisis of meaning.

There is this desire to connect things. I think this can tumble over into the contemporary, paranoid mindset. If Dürer’s engravings and their melancholic effect once served this purpose, the technology may have changed, but the function remains similar. It’s important to trace these connections so we don’t confine ideas to the 17th or 19th century – these are things that are continuous in culture.

GM: You work in different mediums, but you've described yourself as an installation artist and said that your installations work like language and have a syntax. How does installation art have a syntax, and why does that matter?

PKB: It’s about how things are arranged in space, almost like importing the structure of a sentence or paragraph into a spatial experience. What do you see first? What’s the last thing seen? How are you guided through space? In one installation, I arranged elements from left to right in a small room, where the centre felt like the gutter of a book and the walls formed a spread, shaping the entire show around the space itself. That’s the nature of installation art; it isn’t rigidly structured but co-determined by its environment.

GM: One of the central tensions in your work is the relationship between the object and its image – where the image itself also becomes an object. How do you navigate these problematics?

PKB: I can start with an object, then take an image of it. I use the image as an object in installation, [with it] eventually becoming the actual arrangement. Then, as part of the show it will be documented, and it will be turned back into an image again. This constant going back and forth is what interests me. What is the product? What is the end result? I don't think these questions can necessarily be answered. By the conventions of art, there is a work that has a title, a date and a caption – I like that as a formal convention, that we can settle on that, and I'm very particular in my titling.

In a broader sense, if you continue thinking about anything, there’s never really an end. Artworks get rolled up, put away, and over time they can physically deteriorate or shift in meaning and importance. There's a volatility to the value and interpretation of artworks – something less often discussed but central to how I think about them. Any work or image is just one stage in an ongoing process. There’s a stopping point when it’s shown, a moment where the work and I agree to pause. But that doesn’t mean it won’t change after that.

GM: One convention of the internet is that the more an image circulates, the more it loses quality. People may miss the true skill behind your works if they don’t see them in person – they’re highly crafted. I’m curious to know how you think about degradation and loss while creating these works.

PKB: I think about that a lot. I also think about it in relation to perception or reception of artworks. The idea that the audience can only absorb so much within a scattered attention economy. Almost scoldingly, I've been told there's only so much that you can hope for people to understand or to engage with. And so, I'm interested in that; this idea of lowered expectation; the bar is a set for intellectual engagement.

Then you have the presentation – the exhibition, the IRL experience – that’s the traditional circulation. But now, we’re dealing with the instantaneous, the translation of that work into a flat image, sent into a competitive arena of other images. The work is suddenly part of a scroll of makeup ads, ‘Get Ready with Me’ videos, political content and news. This process is strange – the artwork is immediately inserted into a completely different circulatory system than it was made for. So, I’m trying to treat this as a feature, not a bug, by incorporating elements related to that.

GM: I'm curious about the autobiographical element to your work. In the sculptures, as well as the wall works, you use images and objects that have personal significance to you, but there's also no attempt to explain this to the viewer or reader. What happens to your work when its personal references are lost or recontextualised?

PKB: You say that there's no attempt to explain it, and maybe not overtly; I'm not pointing it out verbally, per se, but there's a lot of repetition in my work. I think there are a number of clues as to what something could signify. Meaning develops over time; it’s a durational process.

GM: Do we want to talk about Luigi (Mangione)?

PKB: Yes, I’m interested in this, and I’m using it in my work to explore subjects. The case of Luigi Mangione is seeking a terrorism charge, which is pretty much a top-shelf charge, so it's probably not in your best interest to be posting about that topic favourably. But if you just use objects, can you refer to something in a certain way?

The artworld likes work that is topical and timely. To take something from a news cycle in a facetious way and present it in a sincere and also insincere way is of interest to me. Having a kind of plausible deniability. I don't think anyone would look at this work and immediately know exactly what this is about, and that's fine. That's preferable to me. I think that's more interesting.

GM: I see your work as almost baiting the viewer, almost encouraging them to engage in a kind of conspiracy with the work itself. Both in your work and writing, you’ve explored the idea of conspiracy, which usually has a bad reputation. But I'm curious, can paranoia be good too?

PKB: There's something that Silvia Federici wrote about conspiracy theory, in praise of conspiracy theory: ‘… For as long as there are men who sit and plan deeds that cause any of us to die, no conceptual flight or verbal trick will stop me from concluding they are conspiring against us.’ The difficulty with conspiracy theory lies in its relationship to real historical injustices. The challenge with conspiracy theory is that it often starts with a grain of truth – the truth being that power is asymmetrical. While some conspiracies have targeted marginalised groups, others now weaponise this truth, allowing historically empowered groups to claim victimhood and obscure actual inequities.

I'm interested in the form of conspiracy theory, not the content. I wrote an essay about QAnon for ArtForum which spoke about its relevance. I'm interested in not whether something is true or not, but if it is relevant, and why it resonates. QAnon was gaining interest in 2018-2019, but in 2021 after January 6th, it really broke into the mainstream. I'm interested in the formal qualities of conspiracies. It's not dissimilar to allegory – there's too much information, an abundance of signifiers, but at the same time, a kind of lack of clarity.