‘Main Last’: Orson Heidrich’s Evolving Artform at R.M. Williams

Interview by A-M Journal l Photography by Daniel Goode

Leatherwork prevails as one of history’s oldest crafts. Entangled in matrices of production, manufacturing, and transformation, leather goods simultaneously straddle the worlds of luxury and ubiquity. Enter Orson Heidrich. A Sydney-based multimedia artist, Heidrich’s recent residency at R.M. Williams examines the symbolism and material realities of leather as an expression of national identity, the dressed body, and superior craftsmanship. Materiality is of particular interest to Heidrich, whose artmaking process often unfolds like a palindrome, looping back and forth between abstraction, translation, and realisation. Under Heidrich’s spell, leather, copper, and photography become as mercurial as any other state of matter, mechanised through shape and meaning. His most recent body of work, Main Last, created at the residency, invites us to reconsider how raw materials carry cultural history, labour, and spirit. Below, we chat to Heidrich about his residency and practice.

ARTS-MATTER: Your residency with R.M. Williams placed you inside a space defined by craft, labour, and tradition. What was it like to work within that environment, and how did it shape your understanding of material and process?

ORSON HEIDRICH: The residency with R.M. Williams placed me within an environment in Adelaide where the brand’s iconic boots are still produced today. It was extraordinary to witness the depth of material knowledge held by the craftsmen working there. Many of them were recognised as “master craftsmen” — individuals with thirty or forty years of experience who had rotated through every stage of production and could literally make a boot from start to finish. Speaking with them, I was struck by their intimate understanding of materiality. The leather, the lasts, the soles, the cork lining, and how each component affected the integrity of the final product.

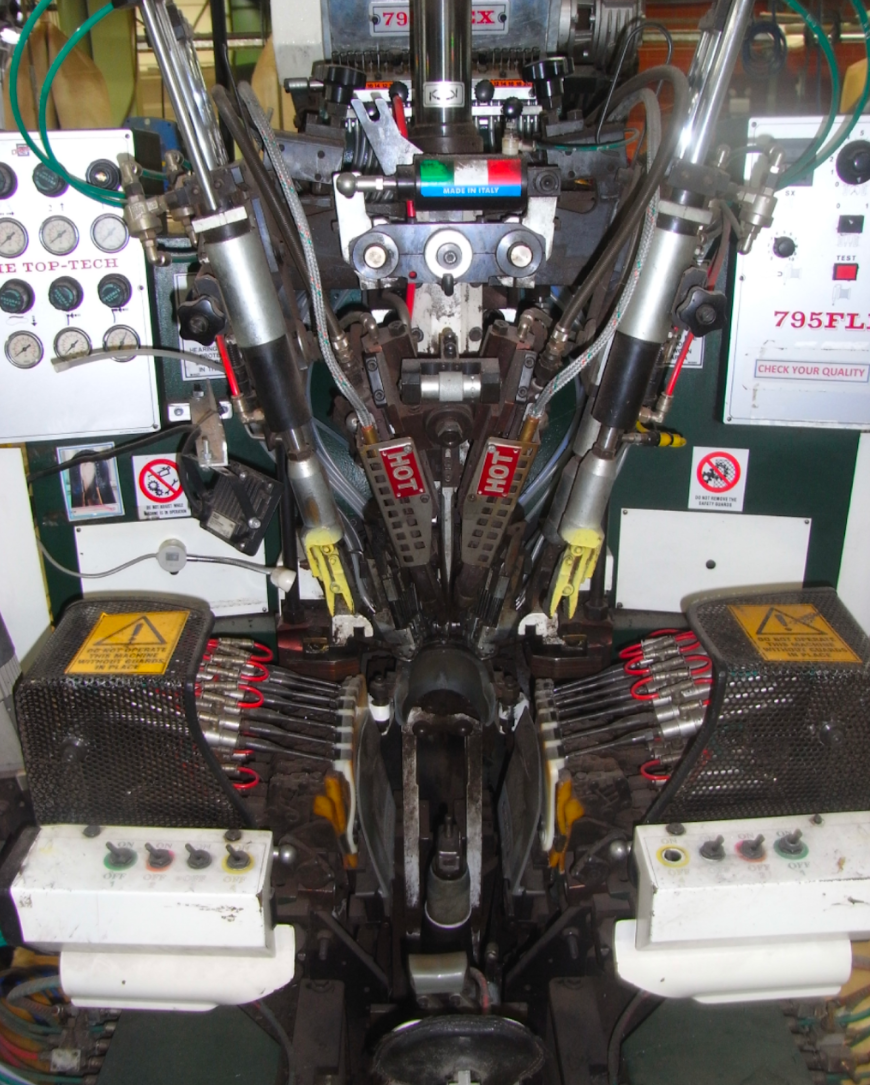

What fascinated me equally was their mechanical knowledge. The R.M. Williams workshop is full of complex, antique-looking machinery — mechanical, not robotic — that feels straight out of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis or Brazil (1985); watching these machines in operation was mesmerising.

My practice often engages with industrial systems and mechanical processes, usually in a more technological or automated context, which I then co-opt and recontextualise to produce contemporary art forms. In this case, though, seeing those same kinds of processes applied to garment manufacturing, a field I’d never previously looked at closely, was inspiring.

It was also uplifting to see how diverse the workshop community has become. While the older generation embodied the archetypal image of Australian tradesmen, the younger cohort represented a broad cross-section of society — a new generation of skilled makers learning the craft locally. Witnessing that transmission of knowledge was both exciting and reassuring, proof that domestic manufacturing and traditional skills still have a living, evolving presence.

A-M: You've described Main Last as a continuation of your Camér series. How did your thinking or approach shift between these two bodies of work?

OH: The work I produced during the residency was titled Main Last — a continuation of my earlier series Camèr, a suite of UV pigment prints on copper created while I was working with the Rural Fire Service as an aerial cameraman. During that period, I was stationed at Camden Rural Airport and only had brief windows at sunrise and sunset to explore my surroundings. I became fascinated by the instruments and tools of aviation; the hangars, the machinery, and the surrounding bushland, much of which had been affected by bushfires.

A-M: R.M. Williams holds a powerful place in Australia’s cultural mythology. How did you navigate or reinterpret those ideas of landscape, labour, and national identity through your own visual language?

OH: Main Last evolved from Camèr through their shared focus on ‘Australiana’ and the Australian landscape — ideas of country, of the bush, and of identity. Whereas Camèr was concerned with aviation and its industrial environments, Main Last turned toward another form of industry: garment manufacturing. Both series are bound by a fascination with the tension between the natural and the industrial — the bush, the boot, the bushfire — each representing a facet of Australia’s iconic rugged cultural identity.

The copper prints in Main Last were created using photographic material gathered on site at the R.M. Williams workshop and the surrounding Kaurna country. Continuing the same process from Camèr, I wanted to capture the intersection between production and landscape. To me, this felt like a natural progression, because both the bush and the boot are such deeply embedded symbols of Australia. I wanted the work to embody both that “rich Australiana” and the quiet presence of country itself, as equal forces in dialogue with one another; and to acknowledge the vast and extraordinary landscape that surrounds us.

A-M: Your practice often blurs the line between documentation and fabrication — translating landscapes through UV printing, metals, and surface treatments. How do you see material translation functioning as a form of storytelling?

OH: My practice often revolves around the intersection of documentation and fabrication. I use photography as the conceptual foundation. A way to gather, frame, and interpret material; and then translate that imagery through industrial fabrication systems, which I adapt or recontextualise to physically produce and materialise the final works. The transformation from image to object, and the abstraction that occurs in that translation, is where my main interest lies. What’s lost, what’s gained, and how meaning shifts through that process are the most compelling parts for me.

For this series, I broke down each photographic image into compositional colour regions, printing them in low opacity over copper so that the material itself could shape the image. In some areas, the copper emerges more strongly, allowing the base material to complete the visual form. This creates a cohesion between image and surface while simultaneously abstracting the form and eroding legibility. Reducing the image to sensation, tone, and atmosphere. That kind of abstraction allows the work to retain a sense of mystery and invitation for the viewer.

A-M: The Australian landscape carries so many layered narratives — of industry, isolation, and belonging. How do you approach these subjects in your work?

OH: In the Camèr series, the Australian landscape became a way for me to navigate feelings of isolation and to reconnect with country. Documenting the aftermath of bushfires was paradoxically grounding; it gave me a sense of belonging and purpose. The act of photographing each day, moving through those ruptured landscapes, became a meditative and cathartic practice that balanced the vastness of both my environment and the solitude of that role. The Australian bush, especially in its raw post-fire state, holds an immense and humbling beauty that compelled my complete attention and reflection.

A-M: Your works incorporate UV printing, base metals, and surface treatments — techniques that feel both industrial and poetic. How did you arrive at these material decisions?

OH: The choice to use UV pigment printing on copper and to incorporate industrial surface treatments ties back to both (photographic) art-historical and conceptual threads in my practice. The process echoes the Orotone, an early photographic technique in which images were printed on copper plates, similar to a Tin-type. While also visually referencing the celluloid 35mm colour negative, with its deep amber hues. By misusing large-format industrial printers, typically reserved for utilitarian use cases such as commercial signage etc, the copper becomes both image and object; the sculptural recipient — a site where light, material, and mechanical process meet. Evoking the same alchemy that occurs when light burns an image into film.

Ultimately, Main Last continues my ongoing exploration of how industry, landscape, and national identity intersect — how material, process, and place can combine to express something both deeply personal and recognisably Australian.