Sir Wayne McGregor & David Hallberg on Technology and the Evolution of Dance

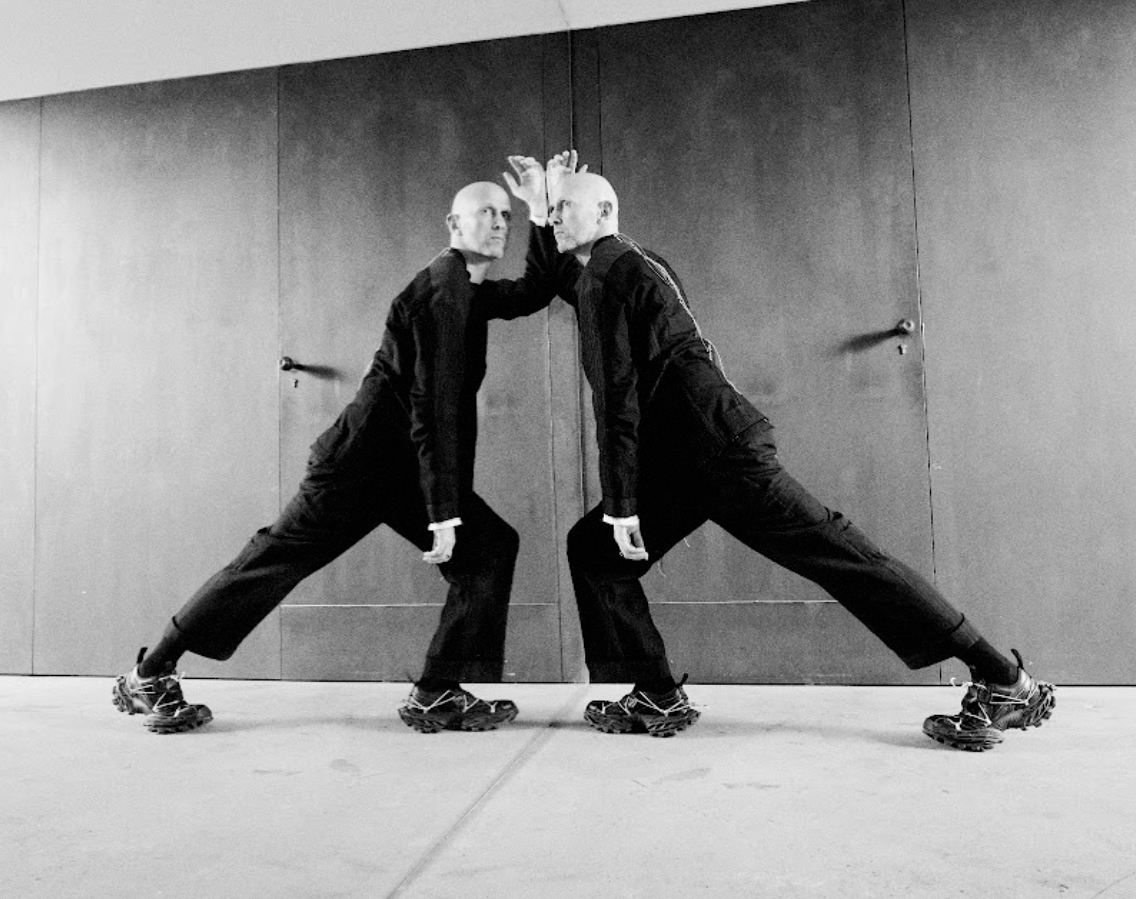

Interview by Jane Albert | Sir Wayne McGregor, photography by Paul Scala | David Hallberg, photography by Justin Ridler

Sir Wayne McGregor is a multi-award-winning British choreographer and director. Resident choreographer at London’s Royal Ballet since 2006 and founder-director of Company Wayne McGregor at London’s Sadler’s Wells Theatre, McGregor is sought after internationally for his contemporary works that challenge the language and movement of classical ballet, regularly experimenting with film, music, visual art, technology, and science. His productions have been performed by the Australian Ballet, the Paris Opera Ballet, the New York City Ballet and the Bolshoi Ballet. Previous collaborators include Jamie xx, Max Richter, Tacita Deane, Jlin, Thom Yorke, Mark Wallinger, Random International and John Pawson. Since 2021, McGregor has been the director of dance at La Biennale di Venezia, and he choreographed ABBA Voyage, a touring concert that launched in 2022 and features virtual avatars of the Swedish pop group.

American David Hallberg has been the artistic director of the Australian Ballet since 2021. The former international ballet sensation was a principal dancer with American Ballet Theatre and Russia’s Bolshoi Ballet (he was the first American to join the Bolshoi as premier dancer), a principal guest artist with Britain’s Royal Ballet and resident guest artist with the Australian Ballet. He has guested with many of the world’s top ballet companies, including the Mariinsky Ballet [Saint Petersburg], the Paris Opéra Ballet and Teatro alla Scala [Milan]. Hallberg is the eighth artistic director of the Australian Ballet and recently renewed his contract until 2030. His directorship to date has been remarkable for his programming of boundary-pushing contemporary works, including appointing the company’s first contemporary resident choreographer, Stephanie Lake, while presenting fresh interpretations of the classics.

McGregor and Hallberg are friends and colleagues. Hallberg was influenced by McGregor’s works for various companies around the world while he was dancing, and he programmed the choreographer’s production, Obsidian Tear, in the Australian Ballet’s 2022 season.

Jane Albert: Where does this interview find you both?

Wayne McGregor: I’m in Hong Kong working on the world’s first 360-degree, 3D immersive environment – a 24-metre screen that wraps around a small audience with holographic dancers. The audience can walk around and feel very present within the space. It’s a very complicated, nightmare project, but in the most amazing way.

David Hallberg: I’m looking at Sydney Harbour right now. We’re in the thick of a true Sydney season in all its highs and lows – eight shows a week for seven weeks; it’s a lot for the dancers, a gruelling schedule – but the company’s great, life is good. And oh my gosh, Sir Wayne, congratulations! I saw your fabulous video and your fabulous outfit [McGregor was recently knighted at Windsor Castle by King Charles for his exceptional contribution to the arts].

WM: Ah, yes, Balenciaga – he didn’t bat an eyelid.

DH: He’s had Vivienne Westwood, Anna Wintour, Stella McCartney, this isn’t his first rodeo!

JA: Wayne, what did you chat about with the King?

WM: We’re lucky in the United Kingdom – we have a monarch and a royal family who are very engaged in the arts and aren’t ashamed to advocate for the arts, so I asked him about the state of the arts in relation to education. It’s really important, because it has been decimated in the UK. We need to do more, and he’s super keen on that, so we had a little chat about that.

JA: Wayne, it's always been a hallmark of your work to look outside the world of dance to technology, music, literature and fashion. Why is that?

WM: I would ask why people are not doing that? If you want to have the conversation about the power of art to change, you need to be doing that in a political dimension, a scientific dimension, a technological dimension, and other artistic dimensions; one can’t just speak in the echo chamber of dance. Dance is an inherently collaborative art form, it’s about interpersonal relationships, how we engage ideas with others, how we think with and through the body, but in a conversation that’s not always about speaking.

All of these things are phenomenal attributes of dance-making that translate easily into other processes. So, if I’m asking a cognitive neuroscientist to work with me, I’m not saying, ‘Will you do something for my dance?’ I’m saying, ‘What are the aspects of dance that would be interesting to you to research to further your study on how the brain models motion? What’s happening cognitively and how can we work together to find some interesting common ground?’.

When collaboration is in the service of the other, it never works; one has to spend the time to work out how one might be able to work out the shared language, then see what that mode of expression is. The work is not just the thing that’s on stage, it’s the whole process up to and onto the stage, and the ripple effect of that more widely.

JA: The world is increasingly concerned with the rapid pace of change when it comes to AI and what it may replace. David, does that play into your discussions about the future of dance?

DH: I’m a huge proponent of live art, and this isn’t a discredit to any other forms, but I don’t feel there’s any threat of AI taking over the art form because the beauty of dance is watching it before your eyes, it’s so momentary. Nothing can replace having people congregate and experience something that yes, is fleeting but is so singular it can’t be replaced by AI, by video. There is nothing [better] in a performative artform than sharing the artform in the moment – from dancers, musicians, crew, wardrobe – on stage with an audience on any given night.

WM: I think that’s interesting though, David, you tell that to the three-million people who have seen ABBA Voyage live. We say this a lot in dance – dance is of the moment, it’s fleeting, but that’s all our lived experience. The collective part of that is really important, and I’m not worried AI will ever replace human performers; it creates a thing called kinaesthetic empathy in people watching, and AI doesn’t currently have a body or any of the sophistication of our sensing system. But I worry when we always have the ‘replacing’ conversation about AI and technology, because these things are completely different.

As technology moves from our screens, it’s becoming more embedded into our world, so over the next five years, the interactive empathetic engagement with bodies and technology is going to be fully physicalised. And that gives us an amazing opportunity in dance, an amazing potential in performance, and in its relationship with technology to dialogue in this way. When I think about technology, I’m not really thinking about performance, I’m thinking about how one might implicitly work with AI in more interesting ways to uncover some of the phenomenal aspects of live dance.

David, as a dancer you had an amazing career. If there could be an archive version of David Hallberg that was an experience where one could walk around David, where he had a real empathetic, physical presence in the space where you got lots of attributes of the performative quality, would that be interesting? Would it be interesting to see Fonteyn in that way? Because that’s been our experience with ABBA, when they come out on stage, you feel they’re really there. It’s not ABBA and it will never replace the real ABBA, but it gets you much closer to the feeling of what it was to have ABBA there with you in the room. Could you imagine yourself in that zone?

DH: Personally, as a dancer, I’m good with what happened; I’ve moved on in a way I don’t feel I need for people to share what my performative career was like. But when I think about seeing some of the dancers I never had the opportunity to watch live, like [Danish ballet dancer] Erik Bruhn, it would be an unbelievable experience. [In terms of the future] what I do think about is the risk of antiquating this very traditional art form, there’s a risk in not evolving to today’s tastes and desires and interests, to get stuck. I spend so much time thinking about what audiences want, and so often hear, ‘audiences want a tutu’, and yes, they might want a tutu, but they don’t only want a tutu. That is a risk as a big organisation – you do have to be bold and interested and curious, stay on the moment.

JA: David, you recently commissioned British choreographer Christopher Wheeldon to create Oscar, a new ballet about the seminal but tumultuous life of satirist Oscar Wilde. It was also classical ballet’s first mainstage queer love story – is that considered bold and of the moment?

DH: My initial conversation with Chris was that I want to tell stories that today’s audiences can really resonate with, that the ballet world maybe hasn’t told before. It’s not shock for shock value, because that doesn’t last. Truth be told, I don’t find the storyline of two men in love shocking at all, and I think it was appropriate in a really sensitive and thoughtful way, and well researched, so when we presented it to audiences, it had weight to it, purposeful intention. So when ‘Oscar’ and other characters were doing things on stage that might be considered shocking, it wasn’t, because you looked at the whole picture: orchestrally, costume, storyline, choreographically and the dancers’ commitment and belief in it. That’s why I think it resonated with audiences, because it had a proper intention.

WM: I didn’t see the work, so I can’t comment on it directly, but what you managed to do very well was contextualise the work, and this is a really important aspect in moving ballet forward: how do you generate the conversation? How do you get people to start thinking about their biases or prejudices by exploring specific issues in a ballet? The ballet world is very siloed, so what was really interesting to me was that Oscar exploded the conversation in the ballet world. In contemporary dance, gender parity, promiscuity, etcetera is taken for granted, but clearly in the ballet world it isn’t, and that’s really important. Chris had a genuine intention to make something with you that had that kind of intelligence behind it, and it shows you the power of ballet when the medium and message are well aligned.

DH: I think it did two things: audiences who are supporters of the Australian Ballet and have experienced a specific repertoire they love realised there’s other horizons, repertoire or storytelling; on the flip side it brought in an audience who knew of Oscar Wilde or heard of the queer storyline, members of the LGBTQI+ community who haven’t necessarily ever seen a ballet. And that’s when one of the sweet spots is hit. I respect our longstanding audience and want to push them a little as well as give them what they want, but I also want to bring in an audience that connects with the art form in a way they’ve never felt they could connect with it previously.

WM: That’s incredible. That’s really important.