"Art Is My Church": Helen Molesworth on Faith, Ethics, and Radicalism

Interview by Michelle Grey | Photography by Brigitte Lacombe

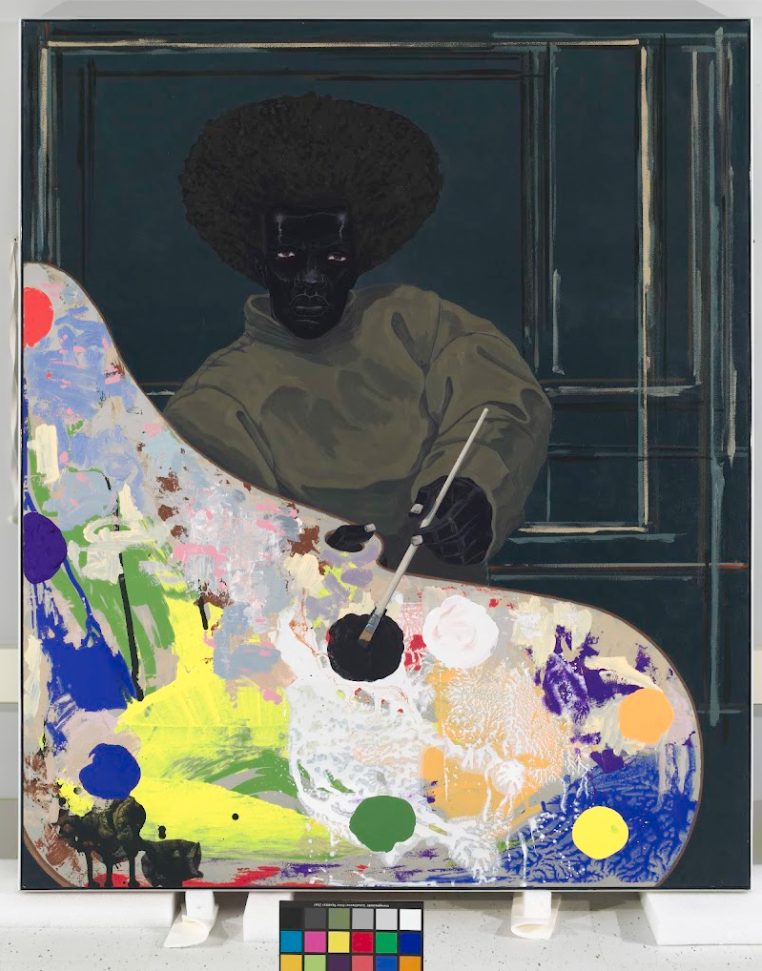

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Richard Norton Memorial Fund and purchase through the generosity of Nancy B. Tieken, © Kerry James Marshall, Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2008.233

Helen Molesworth combines a profound knowledge of art history with a keen sensitivity to how contemporary artists both build upon tradition and offer critical insight into the present moment. Based in Los Angeles, she has held major curatorial roles at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) Los Angeles, the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) Boston, the Wexner Center for the Arts, the Harvard Art Museums and the Baltimore Museum of Art. Across these institutions, she has staged critically acclaimed exhibitions – both solo and group – that blend historical depth with political urgency.

Molesworth is known for her fierce commitment to the ethical, political and aesthetic power of the art object. For Molesworth, artworks are not merely beautiful things – they are vehicles for empathy, inquiry and transformation.

In my conversation with Molesworth, she discusses her profound belief in the power of art, her nuanced relationship with the term ‘activist’, and her thoughts on legacy, beauty and institutional reform. Guided by a profound sense of care and intellectual rigour, Molesworth continues to ask how museums can reflect the world more justly, and how art can help us imagine a more equitable and empathetic future.

Michelle Grey: Your curatorial projects push the boundaries of art history and institutional norms. There are activist, feminist and other various value-driven titles for your projects. How would you describe your curatorial ethos?

Helen Molesworth: First and foremost, I'm a true believer. I have an unfortunate missionary sense of zeal about what I think art objects do. I believe art objects do a constellation of things that I'm interested in. One is that they offer a set of questions, which can be formal, political or personal. They can be research-based or question-driven by one's own needs, feelings and ideas, as well as one's curiosity. I believe in the art object as a communicative event. I'm very interested in the history of art as a series of objects that have been made – I deal with Western art – in the West, starting sometime in the late 1400s and moving through the present.

That history, in and of itself, is also fascinating, because every contemporary artist that I know, working today, is engaged in some form of historical dialogue with artists who are long gone, or objects that are centuries old. And so I think art objects allow for a particular kind of time travel. They allow us to imagine the past, the present and the future. I find that extremely powerful.

Another thing that I think I'm drawn to about the art object is that it's counter to my strengths. I have an extraordinary facility with language, but I am interested in the things that language can't articulate, ergo the work of art. I'm interested in the tension between a form of communication that exists outside of the linguistic but is always being talked about within linguistic terms, because that's how humans communicate. That conundrum is also very powerful to me.

“Art objects allow for a particular kind of time travel. They allow us to imagine the past, the present and the future.”

MG: Interestingly, you use the word ‘missionary’ to explain your curatorial approach. Can you expand on that?

HM: It's interesting, when I use the word missionary, I use it against myself in a way. I'm very aware of the long association between art and religion in the West and non-Western cultures as well. The production of artefacts and spiritual beliefs tends to go hand in hand in all cultures, even those that have a prohibition on it. When I say missionary, what I mean is that I'm sometimes embarrassed by the degree of my own belief and my own zeal or my own faith in something I cannot prove. I often feel like I'm trying to convert people into art lovers. I use the term in a somewhat cheeky way, but also to acknowledge that I am involved in a faith or belief structure; art is my church. I think that's more of an engine for what I've done sometimes than I or others might want to imagine.

MG: You have often been described as an activist. Is this a label that resonates with you?

HM: I don't consider myself an activist. I know everyone says it, but I'm not sure what they mean. I have advocated for the reform of museums because the structure of museums was essentially colonialist, which meant it was racist and sexist. However, I'm also someone who possesses an enormous amount of expertise. In the wake of DEI, [Diversity, Equity and Inclusion] many of us had a desire to change the overarching Whiteness and maleness of our museums. Some said, 'Let the guards curate the show'. And I have to say, I have no interest in that. I love expertise.

MG: Does this mean you think the idea of democratising art is not necessarily the right way to go?

HM: I'm up for democratising access – I don't think you should have to pay to get in. I'm up for democratising the people who work in museums. It shouldn't be only White people or affluent individuals who work there. I'm up for that kind of democratising, but I'm not up for throwing out the expertise of the registrar, the conservator, the curator and the artist. I enjoy professional sports, and I'm a fan of the [fashion] designer Jonathan Anderson. I appreciate individuals who excel in their respective fields. I think sometimes people misconstrue what I'm after; what I'm after is an art world that looks like America. What I'm after is a museum culture that reflects America, not the predominance of a tiny, homogeneous group of people referred to as artists.

“I don’t think museums can be radical spaces. I think they are, in their nature, fundamentally conservative institutions.”

MG: Touching on this idea of modernising or revolutionising museums, do you think that a museum can still be a radical space?

HM: I don't think museums can be radical spaces. I think they are, in their nature, fundamentally conservative institutions. A museum's primary mission, for collecting institutions, is to determine which artworks of a given moment are worth saving. And saving things is not particularly radical. Saving things, it seems to me, is conservative. I don't lean into radicality in that way. If I've engaged in anything radical, it is to insist that the whole world, all of humankind, exists under the regime of patriarchy and capitalism, and trying to unstitch some of those power arrangements is all I have ever tried to do. Because patriarchy and capitalism are so dominant, I am considered radical, but I don't feel radical.

MG: Museums can indeed exist without patriarchy, but do you agree it would be difficult for them to exist without capitalism?

HM: I was just proofreading a podcast that's about to come out where the person I'm interviewing is saying that socialism is the only way. And I actually say, 'I no longer believe that’. The reality of my life as a gay woman is that the rights that I have been afforded have been offered under the regime of capitalism, and I haven't seen those rights provided to anybody else under other economic and political power structures. Capitalism is what we’ve got. I don't like it. It's clearly diabolical for the planet. I am not here to overturn capitalism. I am here to explore ways to ensure human beings are treated equitably.

MG: You've worked on many exhibitions that engage with deeply sensitive subjects, including during the AIDS crisis. When dealing with trauma and suffering in a space that is inherently visual – and often beautiful – how do you approach the challenge of honouring the weight of that material without simply aestheticising it? How do you navigate this kind of terrain with care and responsibility?

HM: I think care and responsibility are key words. I guess when one is making an exhibition or making any kind of space in which the public will enter, the way I always think about it is in terms of hospitality. What does it feel like to come through the front door? What does it feel like to look at the map? What does it feel like to walk into a space? Those are ways of grounding people and preparing them for what they're about to see – whether what they're about to see is a beautiful Joan Mitchell painting or the devastating image by General Idea of Felix [Partz] dying of AIDS on his bedside. Both of those things mandate preparation, and that's part of the role.

To go back to the long and profound relationship in the West between the church and art, we Westerners look at pictures of a man being tortured on a cross all the time. The aestheticisation of violence is something we do in the West. We've been doing it for centuries. So, it's not new. Sometimes I think the shock and the scandal about it is actually a profound form of denial of history, that this is something we have been doing for hundreds of years.

MG: That's an interesting and probative idea that I haven't heard articulated like that before. What draws you to a particular artist's work?

HM: I'm almost 60, so I know what gets me going at this point in my life. I'm very curious about things that I don't understand. If I see something and I don't understand it, that's an indicator for me that it's a place to look and think.

In contradiction to what I just said, I'm also very interested in things that are beautifully done, beautifully rendered and skilfully made. I'm interested in people who make images that show to me that they have a deep investment in the history of pictures. Catherine Opie, Amy Sillman, Kerry James Marshall, these are people who, when you look at their work, you know they've been looking at other artists' work – that they're having a dialogue over historical time. That interests me immensely. I'm interested in artists who work from the kind of terroir of their place.

For instance, Kerry James Marshall's paintings often possess the quality of the American Midwest, characterised by a vast open sky and a low, flat horizon line. He's from Chicago, where he drives by Lake Michigan every day. Sometimes you can feel that in his paintings, and I love that kind of work that has a relationship to the place where it's made. I'm interested in artwork that is asking us to come along with someone in their curiosity about who they are and who we are and how the world works, which is another way of saying I'm interested in works of art that are concerned with the problem of how we relate to each other equitably.

“I hope that in the future we will tell the history of museums less. I fear this may sound contentious, but I don’t mean it to be: I hope we will discuss less who donated the works of art to a museum and more about who chose them.”

MG: What are your feelings about beautiful art for beauty's sake? Or do you think it’s more important that art has a narrative or an underlying message?

HM: I was raised intellectually under the rubric of postmodernism, and we thought everything was political. I can look at a Jackson Pollock and think it's very beautiful, and I can also spin a tale about its relationship to the atomic bomb. It's so corny, but I am of the generation in which we just thought everything was political. There's no outside. There's no outside of patriarchy, of capitalism, of wealth, of income disparity; there's no outside of the climate crisis. So we found ways to have our beauty and eat it too, so to speak. I've always been very interested in visual pleasure. And pleasure is a smarter word for me to use than beauty, because beauty truly is in the eye of the beholder, but pleasure also has an ethics.

MG: As a curator, writer, advocate and human being, what kind of legacy do you hope to leave behind? When it’s all said and done, what would feel meaningful to you to have contributed?

HM: I haven't thought about legacy very much. I can tell you the things that matter to me when people say them to me. When people tell me that they teach my work in their classes, or that they read my work when they were a student, I love that. That makes me feel like something I've done in the museum space has entered the academic space, and that it mattered enough to be discussed and debated, and can break through, showing that it wasn't just entertainment. Like a good show is an excellent form of entertainment, but then that good show's exhibition catalogue would be taught at school – that's pretty sweet. I can't lie – I really, really like that.

I hope that in the future we will tell the history of museums less. I fear this may sound contentious, but I don't mean it to be: I hope we will discuss less who donated the works of art to a museum and more about who chose them. One of the things I've tried to do in every institution I've worked in that was a collecting institution was to make exemplary acquisitions. Other curators and I know who bought what for the museums – we know who went out and fought hard for that Ana Mendieta, that Jeff Wall. That's a fantastic way of looking at who a curator is. One day in the future, someone will put all that together and see that my interests have been relatively consistent, and that the legacy I have tried to leave is to create a lasting mark in permanent collections.