An Unconventional Route to Befriending with Jill Magid and Nicholas Mangan

Words by Karen Leong

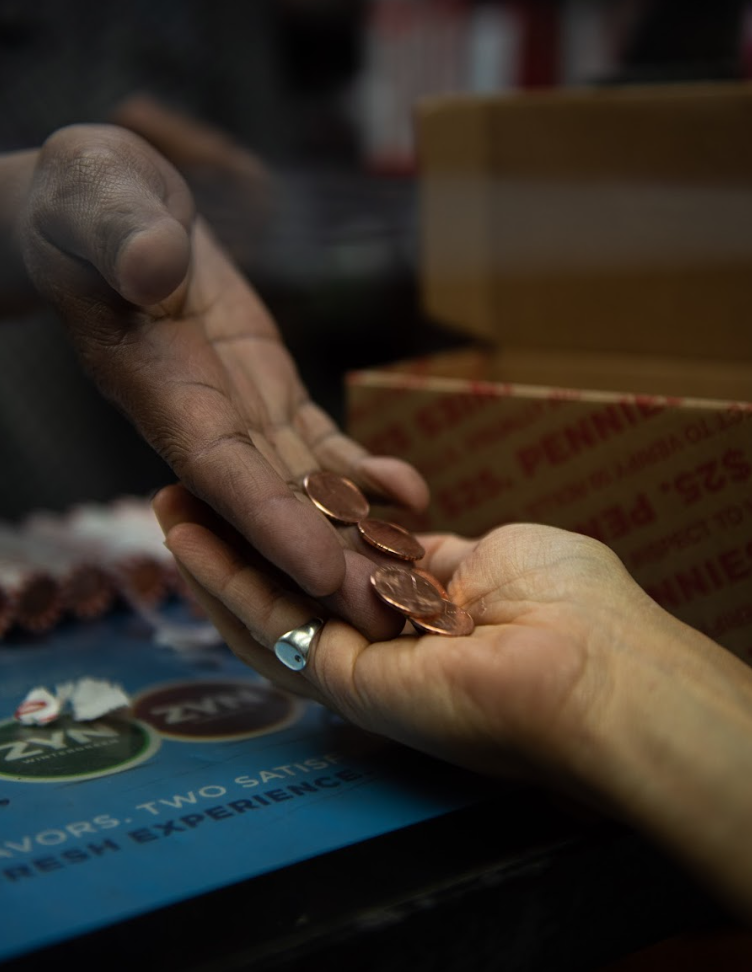

Jill Magid, Tender, 2020, 120,000 edge-engraved 2020 US pennies, photograph by Leandro Justen, image courtesy of the artist, © Jill Magid

Swedish writer Henrik Karlsson believes that a person cannot be contained in the ideas about them. In Dostoevsky as lover, he is quoted as saying, “You can only ever know another individual if you meet them in open dialogue – if you treat them as unfinished, capable of surprise”. Artists Jill Magid and Nicholas Mangan’s communion is one that unites Karlsson’s belief. Over the screen, the two artists forged a bond across seas and became vocal supporters of one another, despite never having met.

Nicholas Mangan’s body of work is a localisation of history and time. He studies the beats of colonialism and violence in order to interrogate the sociocultural in humanity’s ecosystem. His creations think with the raw materials he apprehends. This diffusive output is evident across his discipline. His 2010 artwork, Notes from a Cretaceous World, considers the island of Nauru itself as a sculpture. On his deathbed, the island’s former president had a plan for cracking into the western world. This wish became Mangan’s working methodology. His body of work features a coral limestone coffee table crafted from the island's remaining coral rock, intended for sale on the US Market. Notes from a Cretaceous World’ is the enactment of this matter, questioning the dynamics of power at play from perceptivity alone. In the words of Jill Magid, “His coffee table is not innocent”.

Jill Magid’s oeuvre is a little different. The American sculptor, filmmaker and conceptual artist embeds herself into her work – in a literal and figurative sense. “I can only truly understand a system of government or corporate control by embedding myself into these structures, and creating a dialogue with them,” she explains. “To do this, I have to learn the language of a system and find a loophole in it. I enter systems to ask questions of them. For instance, to a police-run CCTV surveillance system, I ask it to watch and hold me on the system and then make films with the footage. This way of working requires that I use my body to perform a role. My projects are often love stories with power plays.”

Both artists wrestle with control – or the absence of it. Collectively, their work is a question of agency. There’s also a ceding of control within the conditional outset of their process. Magid says: “I have to be constantly open and creative, as one might be playing a complicated game. I enjoy seeing how Nick also sets conditions to lose control.”

The pair spoke to A-M Journal about their ways of thinking and visual language across the mediums of image-making, sculpture and beyond.

How does your private and working relationship differ? Do these intimacies intersect?

Jill Magid: As Nick said, our relationship is through work. That does not preclude intimacies. Through Nick’s process, I feel I know what excites him and makes him think. His objects are so loaded that they explode in meaning. His work is not illustrative of a story; instead, the work he makes pushes the narrative forward. The materials he uses are drawn from the world in which he finds them, and then he transforms them, bringing a historical event into the present, in a novel way.

Nicholas Mangan: I’ve learned more about what’s at stake in Jill's work. I’ve learned how courageous Jill is and the extent to which she will realise her projects. We are different because I’ve always avoided direct use of the human body in my work. But Jill deals with that so rigorously and uniquely. She literally puts her own body on the line. The idea that her actual body will be cremated and turned into a diamond that is made available for purchase – this is a radical gesture that opens up so many questions.

On their commonalities

NM: We are modern pen pals. There’s a commonality in our work – which is an unconventional route to befriending.

JM: Exactly. I think I reached out after seeing Nicholas’ work, Ancient Lights (2015) at our gallery, Labor, in Mexico City. We are supporters of each other’s practice and write to each other about specific projects.

NM: It’s not the exhibition space that is the site for Jill’s work, but the world. I think Jill's work is also within the body. It’s an interesting assemblage. Jill's work deals with value, currency and various kinds of transactions in creative and critical ways.

JMl: I screen Nick’s films for my Sculpture students at Cooper Union [in New York]. Within his films, he transforms and encapsulates his experience, research, and artistic practice into a nonlinear story. His process, like my own, is a way of thinking, making and story-producing.

On making sense out of mediums

NM: The mediums I work with are primarily dictated by the antidote or historical narrative I’m exploring. It’s about how mediums are handled. For example, I converted a diesel generator to run on coconut oil, which I produced in a makeshift refinery. This, in turn, powered a projector that screened a film made of re-edited archival footage from the Bougainville Civil War. The focus was on hand gestures, the cuts into the landscape for the Panguna copper mine, and the slicing of coconuts used by the revolutionary army as an alternative fuel source when mainland Papua New Guinea shut off their supply.

My focus on hand gestures and actions was inspired by the 1959 film Pickpocket by Robert Bresson, which I recently learned inspired Jill’s Tender 2000 film. In Jill's film, we see the conveyance of currency and of movement of matter and the intervention into a system, where language and currency are reiterated.

JM: I was originally a painter but got frustrated because I felt like I was painting about things I wanted to understand in society, rather than directly engaging them. I work in a variety of media: text, image, film, sculpture. The materials I use in my sculptures are often like Trojan horses; they work on a formal level but also enter a system to provoke a question. Like the diamond I will be when I die, that piece asks what it means for an artist’s body to become a commodity on the art market.

On the favourite works of one another

JM: Dowiyogo’s Ancient Coral Coffee Table (2009-2010) is one, but I have many. Ancient Lights is the project of his that I first saw at Labor in Mexico City. I entered the gallery at the moment in the film when a Mexican 10-peso coin was spinning in high definition. The beauty of the image seduced me deeper into the project, which explores the energy-giving properties of the sun – and yet so much more. I love how his work is both visually stunning and conceptually rigorous.

NM: The Proposal (2018) and Jill’s Tender projects are articulated through discrete objects. They’re also expressed through filmmaking. It’s seen in a timeline, and that becomes activated rather than something stagnant. It is both a discrete focus and open, connected to the broader workings of the world. I'm intrigued by the interplay of sculpture and film that Jill manages to harness.