Remaining Radical with RoseLee Goldberg and Yvonne Rainer

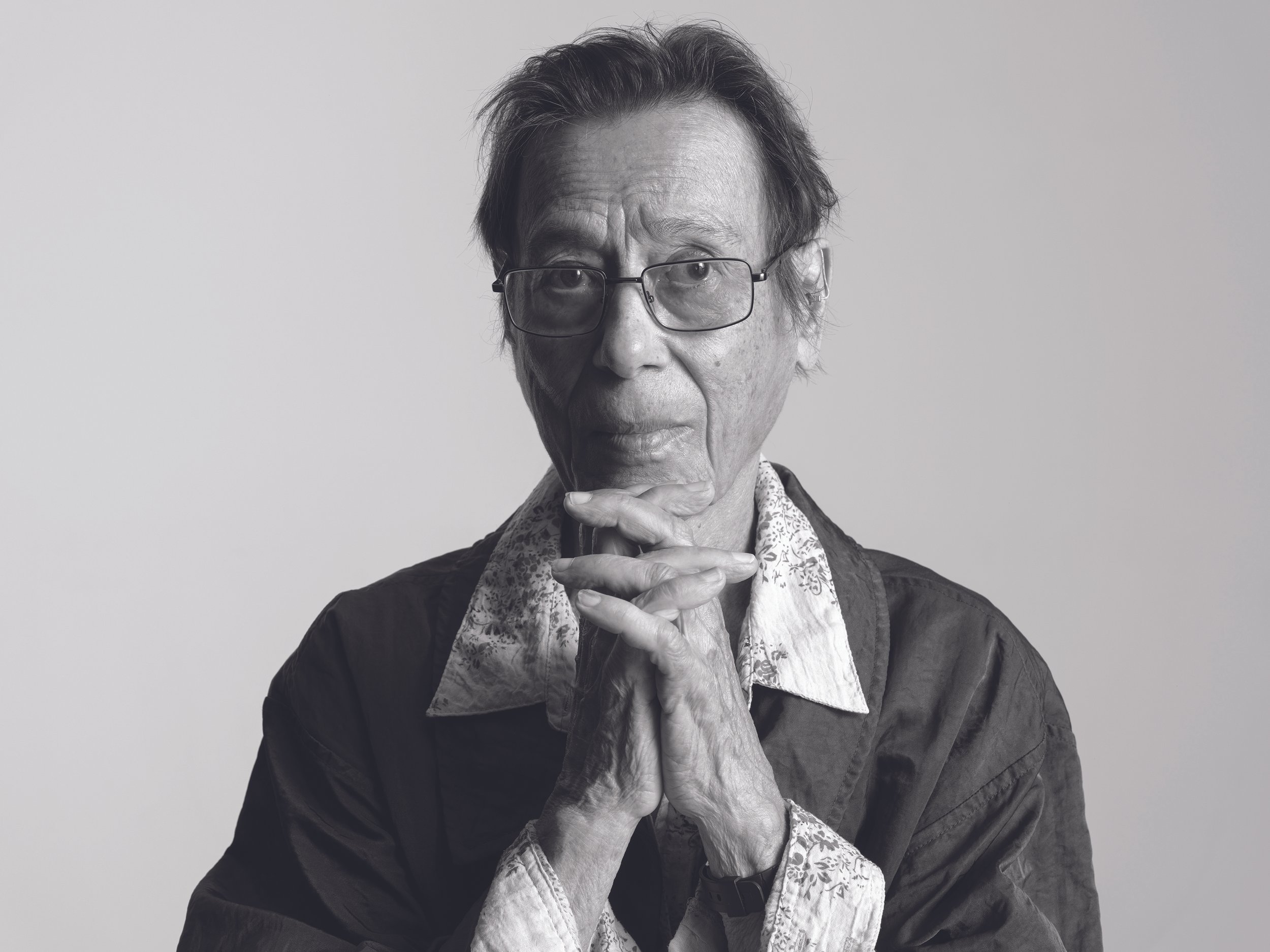

Interview by Davide Di Giovanni | Photography by Brigitte Lacombe

American dancer, choreographer, filmmaker and writer Yvonne Rainer is arguably one of the most influential artistic figures of the past 50 years. Her work has been foundational across multiple disciplines and movements – from dance, cinema and feminism to minimalism, conceptual art and postmodernism.

Rainer’s close friend and collaborator, RoseLee Goldberg, is an art historian and Founding Director and Chief Curator of Performa, which presents a three-week program of live performance across New York City every two years and has commissioned several of Rainer’s works in recent years.

A-M Journal invited Davide Di Giovanni – dancer, choreographer and Artistic Director of NON (New Old Now), a Sydney-based collective that challenges contemporary performance and questions systemic norms within dance – to chat with two of the most seminal and pioneering voices in dance, film and performance art.

Davide Di Giovanni: RoseLee, what do you look for when you experience performance art?

RoseLee Goldberg: Well, it's interesting because probably above everything I'm an art historian, and historians tend to look at everything through a lens that's about the past, the present and the future. And maybe it has to satisfy all those points because when you look at something your mind automatically goes to, ‘Have I seen this movement before’, or ‘Where does it come from?’, and then somehow there’s a little part of my mind that says, ‘I wonder if this will mean something five years from now’.

It's like the past, present and future is always on my mind – it's the way I look at work. But I also try to let go of that and often think, ‘Okay, I know too much’.

DD: Often when I go to a performance with my mother or a friend, they always think I know so much more about it than they do, and therefore have a better understanding of the work. And I think, well I wish I didn’t, because I feel like when I watch a performance, I want to be a blank canvas, where the artist can just tell me everything.

RG: Yes, sometimes I try not to say anything if I'm watching it with someone else – I let them tell me what they think first. But I also grew up as a dancer from the time I was very little, so I think that shapes the way you read something.

The language of choreography is so interesting. You know there's an intelligence that goes beyond what you're looking at, and of course there is such a broad range of history in dance, and especially dance as it spills into the art world. I'm really interested in that edge between visual art and what happens when somebody sits on that edge, and of course [US dancer and choreographer, William] Forsythe has a lot of that. He sits on that edge between visual art, and he understands the sort of avant-garde as it comes through the art world, and he very cleverly articulates both sides.

So, again there is a huge amount of history in the way that he thinks about dance. And then the context for Yvonne was so powerful to be part of New York in the late sixties, early seventies because what characterises that time is this amazing connection between dancers, filmmakers, musicians and poets – the crossover and a similar kind of refusal to play by the rules, or a decision to move away from the classic and traditional history.

DD: Yvonne, how much are you conditioned by art/dance while watching a performance? Do you wish you had no knowledge or education about art so you can experience all the emotions without past references?

Yvonne Rainer: If you’re talking about putting aside one’s own professional experience while watching others’ choreography, this is impossible for me. I have opinions, which for better or worse, may have congealed a little over the years, but I am often delighted and surprised as a dance spectator. The reason I left choreography for filmmaking was not disillusion with the profession as a whole but rather with sensing the formal limits of my own choreographic efforts, which would be replaced by ambitions to deal with more political subject matter, like feminism, the environment, and sexuality through spoken language, inter-titles, and all the changes of image that film-editing allows.

DD: RoseLee, do you have any connection to time and space when you watch art?

RG: Yes, there’s always a desire to hold onto time – I think most performances last 20 minutes, half an hour, maybe more, and you actually spend time experiencing the performance. But mostly in the art world, there's a statistic that says most people go through a museum and they spend less than 30 seconds on one painting.

DD: Yes, I’ve heard you mention that you wanted people to experience art for longer, which is very interesting because that is exactly what I think when I go to museums.

RG: Yes, and how can you stop people and really have them get close inside the brain of the artist. Interestingly, historians are also trying to get inside the brain of the artist and discover what they are physically feeling as they move through a space.

DD: Negative space is an interesting concept for me – that's why my company is called NON, which is a negative word. And the unknown, the negative space I feel when I generate movement. I love partnering, mostly because it’s about the mechanics of the body that are created through negative space. It’s something that becomes very special, and that’s where the love is born.

RG: There’s a negative space which also remains almost two-dimensional as a picture plane. But then look at [German choreographer] Oskar Schlemmer for example – he talks about the stereometry of space and what he tries to have you imagine is almost a room full of sand, let's say. And even when you blink your eye you shift the space, and when you're dancing and you want to really move space, you really have to imagine that you are pushing a whole world of sand or water. You’re really pushing the space away.

DD: Yvonne, how important are the concepts of time and space for you, and what is their role in your works?

YR: My dances usually last from half an hour to an hour, depending on source material and the limits of my own choreographic inventions of the moment. Spatial considerations vary, of course, with the choreography and number of performers in a given section, which reminds me of an aspect of my dances that has been characteristic for many years – and that is the fact that there are no exits or entrances to and from the wings in my work.

If not ‘dancing’, they sit or stand upstage and watch what’s going on; in other words, they become visible spectators but because they are being watched by the primary audience. They can also be seen as secondary performers.

DD: RoseLee, William Forsythe says that when you're falling into something, you should see where that fall brings you and leads you. Do you think that risk of the unknown is something contemporary artists still explore?

RG: It's actually the underlying vision for my organisation because we commission everything, and most people have never made a live performance before, so it’s 100% risk – their risk, my risk. And 100% trust. I have to trust the artist I’m working with. I know they are going to do something wonderful, and they know that I will not fail, and I will always find a way.

DD: Yvonne, what are your thoughts on technology?

YR: Returning to choreography in 2000 was a relief and a pleasure – technology in both film and dance do not come easy to me; I sometimes call myself a technological dummy. Working with dancers in a studio, compared to working with a camera crew, offers, for me at least, more immediate access to the end product without the frustrations of waiting around for lighting set-ups and laboratories.

DD: Which three words would you both use to describe your world?

YR: Trust, friendship and laughter.

RG: I have a few more than three words. I would say desire for works of wonder. I commission the things that make me delirious. I want to see something that I have never seen before. So, I think the commission for me is interesting, because I have to be knocked out. Like we said at the beginning, we are in the field too much, we see too much, so it’s almost like you can’t be surprised, but then when I am surprised again, it’s unbelievable.

DD: Yvonne, what do you think it means to be an artist today?

YR: I don’t envy young, ambitious choreographers today – my contemporaries and I talked mainly about art, not about success, money, ambition. In fact, if asked, I would have denied being ambitious. On $500 dollars a month from my mother I took three dance classes a day, paid $40 a month in rent for a two-and-a-half-room apartment, went to the theatre and dance performances whenever time allowed, bought clothes and books, and still had money left over at the end of the month. A young choreographer I know doesn’t even take classes anymore, can’t afford it.

DD: RoseLee, what do you see in the future for dance?

RG: We're already in the future. There are some things already brewing. We’re always thinking, ‘How can it be different, how can it be better, how can it be new?’ But the reality is, there is always already something new. And it’s in the discovery. It can be a movement or a gesture, an ability to be able to reconcile so many different things in the body. The body is huge, it is our way to tell stories.