Painting the Figure with George Rouy

Words by Karen Leong | Photography by Paul Phung

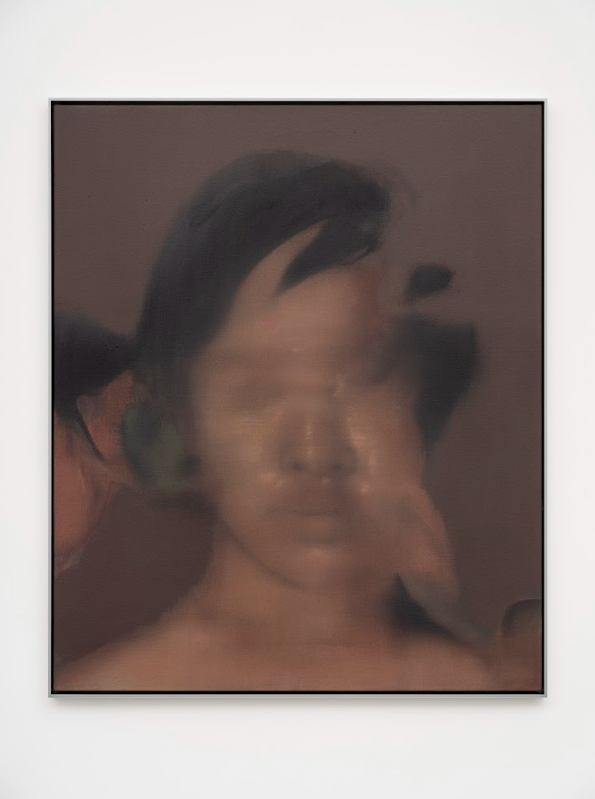

There’s an enduring sense of uncertainty that arises when you look at the work of British artist George Rouy. Oblong figures with distended bodies float against large stretches of taupe and grey, or colours from opposite ends of the spectrum. Then, a face materialises amid the acrylic and linen.

You get the impression of a shapeshifter, though not an anachronistic one. Rouy’s figures hover in constant, serpentine motion. The paintings dissolve unpredictable barriers between the internal and external, bringing forth a singular experience of the figure: in and out of space and place; in and out of time, past, phantom and present; in and out of body and mind.

There’s an acquired intuition within his artistry. Rouy thinks of his paintings as a gateway into meditation. “With the subconscious, it’s more a sense of how you allow room for ideas to pass into this realm,” he explains.

On an atomic level, relationships are about what shifts regarding your own personhood, and his paintings reflect his relationship with his body. He peeks at the nerve endings between these states, and the vacillating aspect of movement and flux. Apart from figurative works, Rouy produces abstract paintings that are interlinked to dance pieces. Each painting is a rendition of time, condensed into a single image. To his eye, movement works. He questions if the paintings are heavy, hot, and exaggerated. Sensorial experience informs the work, with Rouy always thinking about skin, particularly skin on skin.

It seems incongruous that Rouy doesn’t like watching films. He finds it hard to focus and gets fidgety, and there aren’t too many he finds good. The illusion is lost on him very quickly, and he ends up not caring. He does, however, listen to music 24/7 and sound is the antechamber that guides him through his process. He doesn’t dance, but admits to having joined in a little, here and there.

George Rouy, Absence, 2024. Oil and acrylic on linen 240 x 190 x 4 cm (GR0306). © George Rouy Courtesy the artist, Hannah Barry Gallery and Hauser & Wirth London, UK. Photography © Damian Griffiths.

Rouy admits to spending so much time in his studio that it’s now calcified into its own entity... If he can, he goes into the space every day of the week – if he’s in Kent, he’s in the studio. The only times he doesn’t think about painting is when he goes to Paris, where his girlfriend and several friends live. Rouy has lived in both Montmartre and Pigalle, and he doesn’t remember a single restaurant he’s been to. His recommendation? Sitting and having a beer by the canal, which is apparently best enjoyed in spring.

It is a vast and quixotic thing to maintain a hardline boundary by distance alone, but Rouy knows what he’s like as a person. “It’s good to force myself not to be in the same country. It’s very important to do a stint of work, reflect and then go away before you process it and come back,” he observes. “Your decisions come a lot slower, because you have made the time not to do anything at all.” Giving the work a wide berth for a while has become an integral mainstay of his artistic process, allowing him to delve back wholeheartedly when he’s ready.

The regimen has stuck since he committed to full-time artmaking aged 23. He’s 30 now, and the last four years have proven to be a pivotal part of his learning curve. The work itself has taken on new meaning. He has created a whole new fleet of shows and formulated his ideas better. Through that process of call and return, he’s produced a lot of work that he wholly understands.

“You could have eight paintings in a room, and you can test them – and people’s reactivity to them – in a show.” Rouy takes on praise and criticism evenly but cannot help but be intrigued by what people gravitate towards, which is always what he least expects.

When he first started, Rouy held the inward expectation that he needed to be taken seriously, quickly. He expected the smattering of praise, too. When he looks back now, it dawns on him that it’s actually a slow, gradual journey to maturing that he’s still on. His creations, too, needed time to brine. Take a step back to nurture the work, and the work will guide the rest, not the other way around. That was the most significant lesson: that he was anticipating things to spring out of a box way too soon. He took the pedal off himself, and he could enjoy the ride a little more.

Now, Rouy is the youngest artist to be added to the Hauser & Wirth stable. Between his public world of being an artist and his day-to-day, it’s a strange dichotomy to tread. For the most part, he’s on his own. He doesn’t have an assistant or a team working for him. His existence is straddled by quiet work in the studio, and public events, where Rouy admits he ends up spilling the internal monologues he’s had by himself, shored up for days on end. It’s uncanny but useful because the isolation allows him to detach. He’s in the world of his work, and it’s made him more grounded as a person. Rouy says, “The thought of, ‘Oh, I’ve cracked it now’ is never there. There’s always a challenge. With me, there’s always a willingness and drive to learn. I vow to continue to learn.”

It was this willingness that saved him at school. Everything eluded his interest but the creative arts. He spent his adolescence in the art department, and his teacher let him stay during lunchtime and after school. He made the leap to a studio, and the formula and interest stuck. It was what made sense to him, no matter how he felt about himself. He painted through what happened. With art, Rouy remains unfazed.

As with all good things, painting was the first time he fell in and out of love with something. At university, all the tenderness halted to a close. Figurative painting was not in vogue at the time he was studying. “I was lucky that by the time I left, it became relevant again,” he says.

The Renaissance was the first step towards rehabilitation, and Rouy felt comfortable exploring its familiar corner yet again. As he explains, “The paintings at university were all about how painting was dead, and it’s all irrelevant, anyway.” These became fighting words.

George Rouy, Land Sickness, 2025. Oil and acrylic on canvas 250 x 230 x 4 cm (GR0342). © George Rouy Courtesy the artist and Hannah Barry Gallery London, UK. Photography © Damian Griffiths.

None of the propaganda appealed to the artist, and he opted to stick to the figurative genre. It was good that he organised his life around this, anyway, because his work started picking up again as figurative painting located its pulse courtesy of Jenny Saville, Chris Ofili and Peter Doig. Rouy, hoping to add his name to the end of this prestigious list, thinks of his corner of artmaking with vehemence: “There will always be a place for it, because it isn’t tied to the aesthetic.”

This isn’t to say Rouy isn't immune to optics. Lately he’s been looking closely at white in relation to other colours. It’s very cold on the canvas and he’s been wondering how he can achieve brightness with it.

When applied, white on its own cannot lift its own weight – it doesn’t do enough. So, he’s been tinkering with that brightness by adding depth, stippling a mixture of white and yellow. As well as considering which of the two is brighter, he’s been thinking about the inkiness of black paint. Every shade has a different hue. For Rouy, there are certain worlds that live inside these colours alone. He’ll have to tease them out, stroke by stroke.

George Rouy, Flash Thought, 2024. Acrylic and oil on canvas 120 x 100 x 4 cm, 122.8 x 102.3 x 5 cm (framed) (GR0310). © George Rouy Courtesy the artist, Hannah Barry Gallery and Hauser & Wirth London, UK. Photography © Damian Griffiths.