ALL CAPS with Sanford Biggers & Reko Rennie

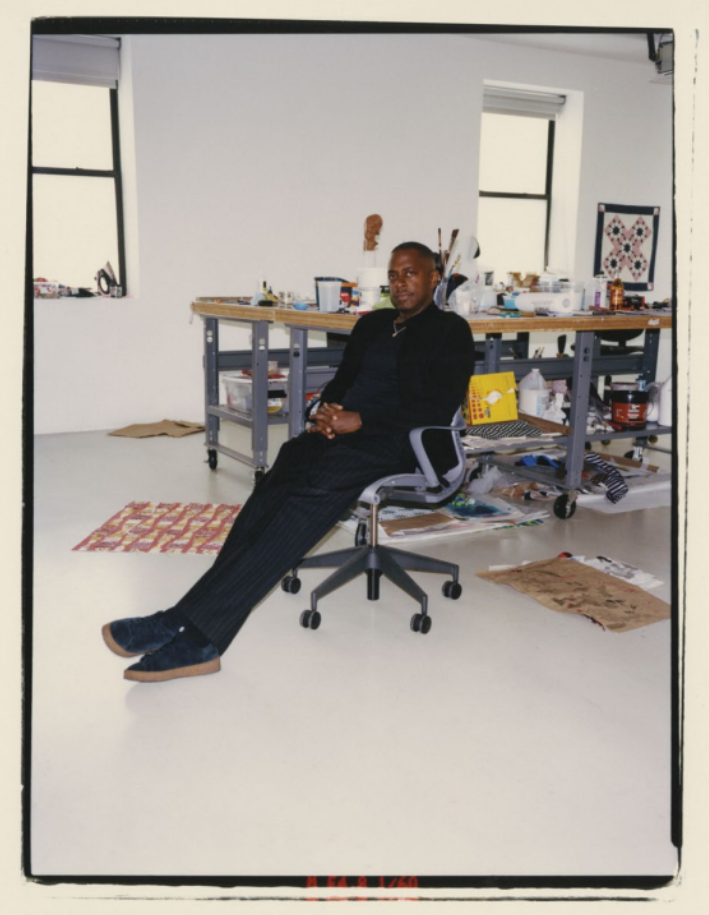

Interview by Sebastian Goldspink | Photographs of Sanford Biggers by Jesse Lizotte | Photographs of Reko Rennie by Jo Duck

“Just remember all caps when you spell the man’s name”, MADVILLAIN, 2003

Sebastian Goldspink, Sydney-based curator and A-M Journal contributor, recently caught up with celebrated US interdisciplinary artist Sanford Biggers and his Australian counterpart, Kamilaroi man Reko Rennie. Their three-way chat covered everything from the influence of hip-hop, politics and the street to creating art in the public realm.

Sebastian Goldspink: Where are you coming to us from, Sanford?

Sanford Biggers: I am in New York City, in the Bronx, right now – in my South Bronx studio.

SG: And Reko, you're in beautiful St Kilda Beach, in Melbourne?

Reko Rennie: I am, I’m on the lands of the Boonwurrung people, the traditional lands of the Boonwurrung.

SG: Sanford, have you ever been to Australia?

SB: I have not. Yeah, I have many, many friends from there, but I've never been. I used to live in Japan, but I never made it to Australia while I was living there for those three years.

SG: Well, now you have an excuse to come down and have some drinks with us. Make sure you prepare though – meditate and fast!

So, Reko, you originally come from a street practice. Making work on the street with aerosol and things like that. And you talk about this great moment where you're young and really into art and visual culture, but fine art kind of eluded you. And then you saw an exhibition of the late great Australian artist Howard Arkley, who used airbrushing in his paintings, and you said that you had this incredible realisation, ‘Shit. I know. I know how he did that’. And it was the first time that you went, ‘Oh, yeah, I could make art’.

Sanford, I wanted to ask, did you have a moment when you were young and that was formative where you were like, ‘Yeah, actually, shit, I can be an artist’?

SB: I started out doing graffiti in Los Angeles in my early teens. I was also doing some drawing and painting at my house, and drawing on people's clothes and doing graffiti on people's jean jackets, and so on. And I think the cops busted me and my parents had to come get me, and the next day I was put in the advanced-placement painting class at my school. So, it was at that point where I started to do oil painting and one of the teachers saw my work and got interested in it, and they offered me a solo exhibition in my high-school lobby.

I think that was the first time where there was some outside recognition and it made me feel like, ‘Okay, this is something that apparently I have a talent for and people are paying attention to it’. My cousin was a famous muralist and painter named John Biggers, and we had some prints of his work in my home. And that was also sort of another co-sign that like, oh, people can actually live making art.

SG: It's funny when I speak to graffiti writers in their fifties and they talk about that sort of impulse never leaving you, you know, that kind of thrill. Feeling their pocket for a Sharpie. Is that something that stays with you, Reko? That thrill of the immediacy of making work on the street without any sort of frameworks or sanctions?

RR: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, it was the whole New York scene that permeated here in Australia in the early ’80s. And of course, the book Subway Art, which I stole from the local library like many other kids did in the ’80s. And I took the cover off because it had the beeper, so I got it out and emulated those guys. There is still that element, like last time I was in Redfern, I had a solid marker from Japan. So, it's like one of those kind of waxy crayon-type things that screw out and you can keep it in your pocket and it doesn't get messy, and it's just a habit. Like sometimes I'll bring that, and I put a few little original Aboriginal tags up, or put the Aboriginal flag in a tag format, and yeah, I still love doing it.

My daughter has grown up seeing me do this, and I think that placement of putting something up in a free element, having a little bit of that edge and producing something on the street, it's such an important narrative. Free from these commercial spaces that we occupy as artists, the street has so much power.

SG: Sociologists are dating hip-hop at around 50 years now. And of course, locating it as originating from where you're coming from today, Sanford, there in South Bronx, really this incredible kind of earth-shattering movement that has gone around the world. And Reko, I think it's really interesting from a sort of inner-city Australian perspective, as an Aboriginal man first being exposed to hip-hop and blackness, and not having the same kind of reference points from your own community. Aboriginal people weren't in the media, you couldn't listen to Aboriginal hip-hop back then. This incredible influence of hip-hop globally changed the world.

RR: Absolutely, Seb – you know my story and where I grew up as a kid. A very poor working-class area, a lot like what Brooklyn used to be. Where everyone that had immigrated to Australia from European or Asian countries lived and there’s only five factories to work in, and people that didn't have the ability to read and write could be employed and this is where they lived, in the western suburbs in Footscray, where I was.

For a lot of people that didn't have anything, we had this connection to music, to the street and making art, and the beautiful thing that really permeated and resonated with me was seeing what was happening, particularly in New York and in the Bronx, and in Brooklyn. And seeing how there's this community diversity. There's a representation of all facets of the community – Jewish, African American, Italian, Puerto Rican, Hispanic, like there's this whole connection and brotherhood and sisterhood through music and culture. And that's what I think really solidified that movement for me, and that's what graffiti did too. You know, we used to hang out with a whole diverse community here and we'd be hanging out with people from all over the world. And I think that was something beautiful and inspiring about graffiti.

SG: I think that culture conditions you as well too. Like this sort of concept of all-city of ubiquity and that kind of presence, that kind of drive, it's different. Sanford, do you think that background on the street, that kind of tenacity and that drive has fuelled you seemingly in the opposite kind of realm, like in museums and public spaces?

SB: I think the main thing about it, just like Reko said, is that there's a culture. It's a global culture. I spent time, as I mentioned earlier, living in Japan and in Brazil and Poland and all these places. And there was a point when I'd already started showing in museums and galleries, but I started doing residencies, which would take me to these various countries to do projects. And all my projects were usually somehow hip-hop based, like I'd work with dancers or graffiti artists or DJs or MCs.

And I remember when I started to pitch those projects, a lot of the places that were giving the residencies were like, we don't have hip-hop here. And I would always say, yes, you do. You definitely do, you just don't know it because it was a universal subculture and, anywhere I went, I could find the skateboarders, I could find the breakdancers. If I can find a club, I could find the DJs and then I could find the MCs. So, there were always breadcrumbs in every city, to find that subculture.

That kept me interested in making work that was coming from the energy and that background of hip-hop. And then I got to a point where, and I think this is probably because being from the US and then moving to New York and being sort of at ground zero, that I started to find ways to do the reverse and put it back into the museums.

Not just graffiti in the museums, but the attitude in the museums, and bringing out some of the lesser-known parts of it, like the dance and the fashion or the coded language and all these deeply cultural and almost ethnographic things, and then using the museum to start to recognise it on the same level as they may have recognised Greco-Roman culture, and starting to really try to say, ‘Okay, we know this is on the streets’. We know this is all over the world, but only now are the museums and the academies paying attention to it because they're late to the game.

SG: Sanford, I wanted to ask you about working in the public realm through public art and the legacy of that, and the longevity.

SB: It goes back to the idea of graffiti and making work public and accessible. I think we're both very fortunate that we're able to get the kind of support to do large sculptural and mural projects, but once again, we're serving a much larger audience and it's important to put your style and your twist on it.

For me specifically, and with you as well Reko, I noticed with the patterns and the references there, we're also talking about things that weren't the mainstream museum type of visual language, and bringing those into the public realm in various styles and formats so there's an audience that can get it strictly on the formal and think about it in terms of sculpture. But there's also an audience that’s like, ‘Oh, I know those colours. I know those combinations. I know those marks and those are speaking to me’. And it's good to see that language out there for everyone else to be able to engage with.

SG: It's interesting thinking about museums. In both of your communities, you're really at the foundational kind of phase of access to them. Obviously both Aboriginal art and African-American art has been in museums for decades, but it really is still new in the scheme of things. It’s amazing to be part of that turnaround, but with that comes a lot of responsibility.

One of my favourite stories about you Reko is about your mum taking you during the summer school holidays to the museum because it was free and air-conditioned. It wasn't necessarily about the culture, it was just a free accessible place, and Reko you’re about to do a major career retrospective at that fucking museum. It blows my mind but makes me cry – the beauty of this kid who's marginalised, and then coming back in and running the show!

RR: Powerful. Yeah. Very, very powerful. Thanks, man. Yeah, look, it's a real, real big honour. My mother used to work seven days a week, six days a week and wouldn't have money to take my sister and I on the train – she was in an environment back in the day and this was her escape. She didn't have money, so she used to take us either to the park or the museum, and we would go there and spend a lot of time there during all those formative years.

I think all that time spent just in the museum hanging out obviously imprinted on me, and I used to just deconstruct a lot of the artwork in there as a kid and think, ‘Well, it's really cool having a name up on the wall and doing all that’. I think it just shows the power of influence with art and space and having that access, and going back to what Sanford said about making our works in a public environment.

I think there's a legacy there that we're leaving, and we're seeing a lot of younger crews and younger artists who are seeing what we're doing and achieving, and it's creating pathways to have them say, ‘Look, I've got these ideas. I can do this too’. I've mentored some artists and it's a really important thing for us to have that ability to show these younger crews that they can do whatever they want and just get that support and reach out.

SG: Another thing that I think really binds you guys is the term multidisciplinary. It’s thrown around a lot, but I think with both your practices, you have this kind of urgency where, whatever the medium is or whatever the opportunities, you're going to go for it.

SB: Sure. I think from an early age I was just very curious. There was a part of me that does think that I have a message, and the message I want to share that pushes the culture forward. But then there's the other part of me that, like Reko, was saying, you go to the museum and you start to unpack and analyse all the things there, and you notice something's happening to you when you see the sculpture, and something different might happen from a photograph and something else might happen from a costume or a painting. And you want to see if that message cannot only translate into those different genres, but if those genres offer a different way of communicating to your viewer.

So, for example, if you do an installation or an environment it's sometimes so subtle that the viewer doesn't know exactly what's happening, but their mood has shifted.

The way they move through the space has shifted. All these subtle things happen so that when it is removed, they start to recognise its absence. And that's a huge thing. It's a very subtle thing. And I think it's sort of important because, you know, we are both makers and we know what to do with certain things.

There's the next level where you can just sort of – I don't want to use the word subversively – but sort of subliminally affect people's moods and their behaviour in the kind of way that they don't even catch it till days, months, years later, but it has really had an impact on their life. And I think that's what great art can do. And I think curious artists have to go through those different experiments and those different modes of expression to see how they can communicate through everything that we have available to us.

SG: In my field as a curator, my first exposure to working in art was working on the floor of the museum, interacting with the public and looking at the way that the public navigated spaces. And I've tried to bring that understanding to curating by creating these environments and being really conscious about the end result. But it is dividing line because I know that there's a whole bunch of curators who just couldn't give a shit about that…couldn't really give a shit about what people experienced in the space… they're just doing their thing, and they expect that that people will spend the time reading their boring catalogue essay and unpack the work.

But there is something kind of street level and egalitarian about that kind of position, which is saying, ‘I'm going to reach out to you,’ and in some ways it's both a provocation, but also an embrace simultaneously.

SB: Yeah, I think it is a form of generosity in a way. I also think about that divide. I think about it all the time. I think that somewhere playing between “high culture” and “low culture” has always been part of my practice. I see it in Reko’s work as well. For me, I think there was a moment when graffiti and street art became so popular - Hip Hop culture in general is so ubiquitous. You can go to every culture and you'll see that there was a point where it was illegal, and it was very renegade to do it. But then it got, I don't want to say co-opted because I don't think it's always a bad thing at all, but it has become part of the global cultural fabric, right?

So, then doing that in a museum ended up having the same energy as facing a wall – the museum itself has context. And for me, showing in a museum allowed me to really actually sort of fuck with history…directly with history, because the museum is supposedly the place that is the receptacle of all things that are important and deemed important enough to be taught to current and future generations. So, for us to be able to put our work in there and be able to play with that language, and fuck with that language, puts us on the same level, puts us in the same conversation as anything from antiquity up until everything that's going to come in the future. I think also, I can't speak for Reko, but I am glad that we both are able to work within and outside of those environments.

RR: Yeah, absolutely. They're powerful placeholders and I think we just have to make them work for us, and that's what we're doing. And there still needs to be a lot of change. I'm doing this show now and I'm just making a statement about how, unfortunately, even all our institutions back here still have separate galleries…. Aboriginal art galleries. I mean, it's fucking ridiculous. It’s like this ethnographic study where we're a part of Oceanic and Tribal art, but why aren't we fucking just Australian artists or international contemporary artists, you know? So, you have to be in those spaces and occupy those spaces to make change and to inform.

SG: Once again, this is a very real, live foundational thing. I've had such great amusement over the last week following all the thefts at the British museum. And then this hootspur of the British museum calling upon the public to help them recover the stolen artefacts. And you’re like… you are the burglar… you’re the biggest thief there is.

I think about one of our greatest historical warriors, Pemulwuy, who led this incredible campaign of resistance against the British. They finally got him – he was what they call a cleverman, a man who could see things, a spiritual man. So, when they caught him, because he was so powerful, they cut his head off and put it in a jar, and it’s still in Britain, and we can’t get it back. This is what we're dealing with when we talk about institutions.

So yeah, it is very real. And it’s about fighting those systems of control. And I think that all artists of colour, in those spaces, I don't think they ever take it for granted… you're always kind of watching your back. You're always waiting for the other shoe to drop, right?

SB: Absolutely.

RR: One hundred percent.

SG: And turning that understandable rage and that understandable feeling of inequality into a positive, into something that speaks to a wider community, but also speaks to both of you guys when you were little kids going to those places and going, ‘Oh, wow…I see myself.’ And you can’t underestimate the impact and the importance of that.

RR: Absolutely. It's powerful. Having your work in those spaces you're creating a dialogue for the younger generations to say, ‘I can do this. I can be here.’

SB: Yeah, you’re giving them comfort too. They expect to see it. And, in the long term, it also makes all those institutions say, we can't survive unless we show this work. Because this is what the people want. This is new to them because we hid it for so long.

SG: But it's that thing, isn't it? When you suppress history, it’s like you're holding down this wound and then the blood starts to bubble up. The more you hold it down, the more it comes up. I feel so privileged to be living in a time where we are seeing this change.

I think it’s time to wrap up – Reko and Sanford, thanks for being such incredible artists and warriors for your people as well. It’s been an honour and super fun talking to you guys. Do you have any post thoughts, anything else you’d like to add?

SB: Yeah, I just want to say thank you and that it has been a pleasure learning more about Reko’s work and being able to speak with you both. I feel like we have been in the same fight our entire lives as artists… you know what I mean? Across the seas we have been working on the same vibe, to knock down the same doors, and get this conversation going, and push humanity’s culture forward.

RR: Thank you Sanford and thank you Seb. It’s been lovely to connect, and Sanford your work is always very inspiring, and it’s been lovely to meet you here… I look forward to connecting with you in the future, man.